quarta-feira, 30 de setembro de 2015

Publishers are in peril from annoying ads

There is nothing so inspiring as a person triumphing over disaster — the narrative of many books and films. So the sight of Henry Blodget, the former Wall Street analyst who was disgraced in the 1990s dotcom bubble, selling Business Insider, the news site he founded in 2007, at a valuation of $390m is heartwarming.

Even more remarkably, Mr Blodget has achieved the equivalent of swimming through shark-infested seas by luring millions of readers with brash headlines about market movements (and quite a lot of sober stuff) while funding his enterprise with advertising. He has floated on the choppy, murky waters of online commerce.

The deal shows not only Mr Blodget’s endurance and ingenuity but also the size of the challenge. Axel Springer, the German publisher, is buying a website with 76m monthly users and projected revenues this year of $43m — which amounts to 57 cents per user per year, or 5 cents a month; a modest haul. There are no profits, although they are anticipated in 2018.

These revenues are a fraction of subscription-based businesses such as Netflix, which charges US users $8.99 per month — and Mr Blodget hopes to triple revenues from his own subscription research service by 2018. But it is not his fault that the return from online advertising is so meagre or that the yields are so tiny. Online ads have not delivered the financial rewards that many publishers once expected.

Now they face a revolt by users who are tired of screens being occupied by flashing banners and video ads that play without warning, of personal information being harvested in unknown ways for ad targeting, and of download speeds being sapped by bulky software. About 200m people already use adblocking extensions on their browsers, both for desktops and mobiles.

Ad blocking put paid to $22bn in potential revenue last year, according to one study, and Apple has added to the challenge by approving adblocking applications for its mobile browser. This has provoked complaints from publishers that users are breaking an unwritten contract — they receive free news and information in return for being served ads — and that blocking is unethical.

As someone whose salary is partly met by digital advertising, I do not agree. There is also an unwritten contract between publishers and their readers not to allow advertisers to litter sites with time-wasting and annoying messages. Too many publishers, eager for revenue, have breached it.

This has caused a vicious cycle. Publishers have placed ever more slots for ads on their pages — some in places that consumers are unlikely even to see them — and allowed them to be filled through ad exchanges with limited control over who uses them and how the ads operate. Business Insider gains 30 per cent of its advertising revenues from “programmatic” ad placement.

Even some in the advertising industry express sympathy. “A number of publishers have been so anxious to take every cent from anyone that they have abused the consumer’s trust,” says Rob Norman, chief digital officer of GroupM, the world’s biggest media buying agency. “I see why people use blockers. You would, wouldn’t you?”

Mr Norman’s sympathy does not extend to letting ad blocking continue unabated. He would like Google, one of the biggest beneficiaries of digital advertising, to wield the “big stick” — retaliate against the young, male, technically sophisticated users who disproportionately use ad-blockers by blocking them from seeing YouTube videos and hitting them where it hurts.

But not even Google has the power to change the world by itself. It requires concerted action by publishers to say what kind of adverts they will allow on their sites — standards which can then be approved as legitimate by both advertisers and consumers.

Ad-blocking companies seized the chance, defining what they regard as “acceptable ads” — the kind they will set software not to block. In some cases, they have taken payments from large publishers and ad brokers. Eyeo, which sells the popular Adblock Plus software, then “white-lists” their ads.

This has two problems. One is that standards are influenced by a subset of users with a pronounced antipathy to commerce. A survey of Adblock Plus users found that 21 per cent would not even accept “unobtrusive ads”, while more than half partly or completely agreed that all content should be published free and without ads.

Second, asking for money to unblock ads bears a nasty resemblance to extortion. Eyeo insists that no publisher can buy approval and everyone has to meet the same standard, but it has undermined its own claim to be acting responsibly. It now intends to appoint an independent review board to make these decisions instead.

Publishers, which have a long-term interest in not alienating users, need to impose tighter rules for advertisers themselves. If they do not, the tensions will descend into warfare among advertisers, consumers, ad blockers, and software companies that nullify ad blocking, such as PageFair.

Mr Blodget has navigated his way through testing challenges already, and will remain at Business Insider under its new owner. Perhaps he could offer moral leadership.

John Gapper

Fonte: FT

terça-feira, 29 de setembro de 2015

China data: Making the numbers add up

That China's official economic data cannot be trusted is now received wisdom among western economists, investors and policymakers. To treat the numbers as authoritative is to invite ridicule: believers are naive at best and, at worst, stooges for Communist propaganda.

The problem with this conventional wisdom is that, aside from the closely watched and politically sensitive real gross domestic product growth rate, other official data vividly depict the slowdown in China's economy that sceptics insist is being concealed. If there is a conspiracy to disguise the extent of harder times in China, it is an exceedingly superficial affair.

The surprise devaluation of China's currency in mid-August fuelled scepticism about official GDP data, as many interpreted the move as evidence that Beijing was taking drastic action to rescue an economy in deep trouble.

China officially posted 7 per cent real GDP growth for the first half of 2015, bang on the full-year target that Premier Li Keqiang announced in March. To the sceptics, it was both too convenient and incongruous with other data that suggested a deeper slowdown in manufacturing and residential real estate construction, the country’s economic powerhouses.

Experts on China's national accounts data broadly agree that the quarterly real growth figure is subject to politically motivated “smoothing” aimed at reducing the appearance of sharp swings in the economy, especially in response to external shocks like the Asian financial crisis in 1998 and the global financial crisis in 2008.

This goal is achieved mainly by tweaking the inflation metric used to convert between nominal and real growth, known as the “GDP deflator”. By understating inflation, China's statistics masters can create the impression of faster real growth.

Trend setting

Yet the shortcomings of this single data point do not seriously impede our understanding of trends in the Chinese economy. One need look no further than nominal GDP figures, which express economic output in current prices, without adjusting for inflation, to observe the bleak state of the country's main industries.

“China has some of the least volatile real GDP growth of its kind in the world, but nominal GDP data look more reasonable in a number of key aspects,” Wei Yao, China economist at Société Générale, wrote last month.

Nominal GDP growth in China's industrial sector, which includes manufacturing, mining and utilities, grew at a paltry 1.2 per cent in the second quarter of 2015, down from an average of 5 per cent in 2014. For construction, second-quarter growth was 4.1 per cent compared with 9.8 per cent last year. Meanwhile, services are now the fastest-growing sector of China’s economy.

Nominal growth is more important than its inflation-adjusted counterpart for most purposes. A company making revenue projections, for example, has little use for real growth rates.

Similarly, commodity exporters in Latin America and Africa see the slowdown in Chinese commodity imports reflected in customs data on both import volumes and product value.

The official data are the best out there. There is a range of final [real GDP growth] figures, all of which are equally justifiable

- Carsten Holz, economics professor at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

Carsten Holz, an economics professor at Hong Kong University of Science & Technology who has also taught at Harvard and Stanford, is a stout defender of China's official data. He says Beijing’s use of the deflator as a fudge factor is “intensely annoying to detail-oriented analysts but only marginally relevant for practical purposes”.

He doubts that Mr Li or his deputies directly instruct the National Bureau of Statistics to report a particular growth figure, but he acknowledges that the agency faces pressure to meet targets and avoid stoking economic pessimism. In theory the GDP deflator should be the broadest measure of inflation for all goods and services produced in China, including those not counted in the consumer price index. CPI covers consumables but not investment goods or services like logistics or law.

The official statistics agency provides few details on how the GDP deflator is calculated. But Mr Holz believes that only the five-person Communist party cell within the statistics bureau would be privy to final deliberations. That group includes commissioner Ma Jiantang and his three deputies, including Xu Xianchun, head of the national accounts department.

“Xu Xianchun sits at the table, and he knows, ‘Well, we should push it up a bit if we can.’ He looks at his documents and he says: ‘We can use this deflator, or we can equally justify using that deflator. OK, we're going to use that one because it leads to a tiny bit higher growth rate,’” Mr Holz says.

This is hardly a confidence-inspiring vision of Chinese data compilation. Yet Mr Holz sees no better alternative. He has stress tested the official growth rates using several alternative deflators based on published price indices like CPI and the producer price index, which tracks wholesale goods.

He concludes that China’s average annual real growth rate between 1978 and 2011 — officially 9.8 per cent — may have been as low as 9.1 per cent or as high as 11 per cent. That still leaves the official rate as the best guess.

“I prefer the official data. I think they are the best data out there. I agree that there’s a range of final [real GDP growth] figures, all of which are equally justifiable. The 7.0 [per cent] figure for 2015 could be in an interval of 6.5 to 7.0 per cent or [even] 7.2,” says Mr Holz.

For his part, Mr Xu last month used the People’s Daily, the Communist party mouthpiece, to defend his agency against accusations that the GDP deflator has understated domestic inflation in recent quarters by failing to adjust for the impact of falling commodity prices.

Mr Holz’s most formidable intellectual antagonist is Harry Wu, economics professor at Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo . He first offered an alternative assessment of China’s GDP data in 1995 and has spent 20 years refining his methodology.

His latest research finds that China’s average annual real GDP growth for 1978 to 2014 was 7.1 per cent, 2.5 percentage points below the official estimate of 9.6 per cent. That is more than double the margin for error that Mr Holz calculates. Mr Wu says growth last year was 3.9 per cent, compared with the official figure of 7 per cent.

Mr Wu initially mentored Mr Holz but their intellectual dispute later caused the two to fall out with each other.

“It got to a point where Harry Wu wasn't talking to me and wasn't citing my work,” says Mr Holz. “I didn't agree with his work. It just didn't convince me. I thought it was actually wrong.”

As worries about China’s economy have seized global headlines, analysts in London and Singapore — some new to the study of its national accounts — have weighed in on the data’s reliability.

Michael Parker, economist for Bernstein Research in Hong Kong, is illustrative of that approach, but he disagrees with the sceptics. “The idea of getting tens or maybe hundreds of thousands of accountants and statisticians across China to march consistently in a crooked line — and to do that for a decade or more — sounds, to us, implausible,” he says.

To follow the debate between Mr Wu and Mr Holz, by contrast, is to plunge down a rabbit hole of benchmark revisions, input-output tables and competing hypotheses about productivity growth in the services sector. Few analysts have tried to score the match punch by punch. Yet what is striking is how much the two agree on. In particular, both point to problems with how the NBS, the statistics agency, measures the industrial sector, the backbone of the economy.

The NBS stopped publishing raw figures for industrial output in 2008. Glaring problems had become an embarrassment to the extent that by 2007 monthly production data from large-scale enterprises showed that such output was greater than the total industrial output reflected in quarterly GDP data. Logically, that is not possible.

Such paradoxes are blamed on over-reporting of output by companies and local governments. Local GDP growth has traditionally been an important factor used by the Communist party to evaluate performance and decide who is to be promoted up the ranks, though that is slowly changing.

Where Mr Holz and Mr Wu differ is largely their response to these flaws.

Mr Holz broadly trusts that Mr Xu of the NBS, acting as a gatekeeper, is able to filter out the most glaring over-reporting when his national accounts division receives data from colleagues in the industrial statistics division and transforms it into the industrial component of GDP. For him, nominal GDP figures are mostly accurate, leaving the deflator as the main issue. Mr Wu, by contrast, considers the industrial GDP data irredeemably flawed by the need of local officials to hit targets.

Both men see shortcomings in China’s data collection, but Mr Wu’s calculations diverge from the official data most acutely during crisis periods. His conclusion is that the error is “not mainly caused by methodological deficiencies, but instead by political influences”.

His scepticism propelled him to create a parallel data series for industrial output built around a Soviet-style list of names and quantities of industrial products manufactured in China each year from steel pipes to toasters.

“If local governments want to fabricate or manipulate commodity production stats, they can't do it. There are too many, and it's too complicated. You would need to be professional,” he says.

Industrious truth seeker

To Mr Holz, Mr Wu’s alternative series, which contributes to a much larger downward revision of China's real growth rates over decades, does not offer any improvement over the official data that both agree are flawed.

He argues that it is impossible to reliably derive industrial output in value terms because of difficulties in measuring improvements in product quality and assigning inflation-adjusted prices to newly developed goods. The quality question is crucial for whether price increases are interpreted as additional real output or simply inflation.

Mr Wu says his methodology incorporates reasonable assumptions about product quality and new development. Yet this is an awkward moment for his radical rejection of China's industrial production data. The monthly industrial output series, long viewed as suspect, shows a sharper decline than is reflected in the overall GDP growth rate. Indeed, this incongruity is the biggest source of scepticism about China's true GDP growth rate.

The likelihood that the growth rate is subject to manipulation reflects institutional weakness, notably the lack of independence of the NBS. But it also results from an analytical failing by those who assess China and other economies. If the emphasis on this single number were not so excessive, the incentive to massage it would be less.

The sooner real GDP growth loses its totemic significance, the sooner we are likely to receive more accurate data. For China and other governments for whom economic growth is the main guarantee of political legitimacy, the temptation to fudge will always exist. But in a scenario where China’s economy is in such dire straits, that stability is threatened, relying on a single figure to persuade that things are great is unlikely to prove an effective political strategy.

|

The surest way to sound smart and hard-headed on the issue of Chinese growth in recent months is to cite the so-called Li Keqiang index.

This alternative growth metric is based on comments reportedly made by Mr Li, now premier, to then-US ambassador Clark Randt in 2007, and revealed by WikiLeaks. Mr Li, then party secretary in the north-eastern province of Liaoning, reportedly said data on gross domestic product were ‘man-made’ and therefore unreliable. Instead, he preferred to use three direct indicators of economic activity supposedly less subject to exaggeration: electricity consumption, rail freight volume and bank lending.

Today, the Li Keqiang index is

exhibit 1 for the case that quarterly GDP data are soft-pedaling the extent of the economic slowdown. Other monthly indicators like fixed-asset investment, industrial production and retail sales — which have all slowed more sharply than real GDP over the past year — are similarly offered as evidence for the prosecution.

Yet these metrics fail to capture activity in the services sector, now the fastest growing area of the economy.

“Steel production, for example, is significantly more energy intensive than entertainment, so the demand for electricity has fallen sharply as the structure of the economy has evolved,” Nicholas Lardy, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and an observer of the Chinese economy, wrote last month.

“Assuming that electric power growth is a good proxy for China’s overall economic expansion is like trying to drive a car by looking in the rear-view mirror,” he added. Apart from the long-term evolution of the economy, one-off factors early in 2015 also enabled other sectors of the economy to make up for the decline in smokestack industries.

The stock market boom helped output from financial services increase 27 per cent annually in the second quarter. Yet such growth is certain to have slowed since the stock market rout that began in late June.

|

Gabriel Wildau

Fonte: FT

segunda-feira, 28 de setembro de 2015

Five takeaways from the Catalan elections

Pro-independence parties emerged with a majority of seats in Sunday’s regional election in Catalonia but they fell short of their target to capture 50 per cent of the ballots cast.

The main pro-independence party, Junts pel Si, won just under 40 per cent of the vote and 62 seats in the Catalan parliament, making it the biggest political force in the chamber by far. Together with the 10 seats won by CUP, a far-left pro-secession party, the independence camp will have an absolute majority in the 135-seat regional legislature.

But the two parties together won slightly less than 48 per cent of the regional vote — falling short of the majority they would have needed in a proper independence referendum.

So what are the lessons for the independence debate in Catalonia and for the future plans of president of the region Artur Mas?

The independence camp is reaching a plateau, albeit a high one

After years of intense campaigning, there were doubts over how much more the Catalan pro-independence camp could grow. Sunday’s historic election showed that the movement has continued to expand — but at a much-slower pace.

According to the official result, 1.952m Catalans voted for one of the two pro-independence parties, Junts pel Si and CUP. At last year’s informal independence vote, the number of independence supporters stood at 1.897m. The increase is marginal, and suggests that support for a Catalan secession from Spain is finally reaching a plateau.

On the face of it, that scenario would be worrying for the independence camp, which has yet to show that it has half the regional electorate behind it. What more can it possibly do to sway those it has not yet convinced? But Sunday’s result also holds a clear warning for Madrid: Spain’s government has spent years mocking the independence campaign as a soufflé, ready to collapse at any moment. That has not happened yet, and there is no sign that it will. Both sides, it seems, will have to dig in for a long and difficult battle, in which territorial gains will be measured in inches, not miles.

Almost everyone’s a winner

Elections are supposed to divide politicians into winners and losers. Not on Sunday night. The independence parties were celebrating the fact that they managed to obtain their desired absolute majority in parliament. Their opponents were celebrating the fact that the separatist bloc was kept below 50 per cent of the vote. The anti-independence Ciudadanos party was thrilled to emerge as the second force in Catalan politics, lifting its vote from 8 per cent in 2012 to 18 per cent now. The Socialists surprised themselves by losing fewer voters than they have grown accustomed to. The conservative Popular party fared badly — but can console itself with its resurgence at national level. The PP’s eyes are firmly on the general elections in December, where it will present itself as the principled defender of Spanish unity. Whatever tensions arise between Barcelona and Madrid in the next weeks will probably play into its hands.

What happened to Podemos?

The rise of the awkward Catalan kingmakerSpain’s new anti-austerity movement was not on the ballot. Instead, it threw in its lot with other leftwing groups to form Catalunya Si Que Es Pot, or Catalonia Yes It Is Possible. The result was a severe disappointment. The alliance scored just 9 per cent of the vote, and 11 seats in parliament — a poor performance when measured against Podemos’s backing at national level or the movement’s recent triumphs in local elections in Barcelona and Madrid. Part of the problem was clearly made-in-Catalonia, starting with the party´s little-known lead candidate and the remarkably cumbersome name (abbreviated to the no less cumbersome CSQEP). The attempt to steer a middle way between the pro- and anti-independence camp also appears to have backfired. But the disappointment on Sunday night will undoubtedly raise broader questions: Is the novelty effect and excitement of Spain’s radical new-left wearing off? Have Greece’s economic travails harmed the standing of Syriza party´s closest ally in Europe? Podemos, and Spain, will find out two months from now, when the country holds general elections.

The Popular Unity Candidacy, or CUP, is a small party with a big role to play after Sunday night. It supports the creation of an independent Catalan republic, but campaigned separately from Junts pel Si, the joint list formed by the region’s two main pro-independence parties. This is where it gets complicated. The CUP’s 10 seats count towards the pro-independence bloc, but it has a very different idea of what an independent Catalan state should look like. Its manifesto promises to take Catalonia out of the EU, out of the Eurozone and out of Nato. It supports the nationalisation of key industries and more state intervention in the banking sector. Crucially, it has also made clear that it will not support Artur Mas, the Catalan president, for another term in office. The other pro-independence parties, however, want Mr Mas to continue in his job. The dilemma here is clear for both sides: the pro-independence camp can only claim to have a majority in parliament if Junts pel Si and the CUP are united. And there is, at least for now, no real indication that the CUP´s radical agenda can be reconciled with the conservative base that supports Mr Mas.

Still heading for a crash, sometime

Mr Mas and his allies made clear on Sunday that they now feel emboldened to press ahead with a controversial plan to separate Catalonia from Spain over the next 18 months. Winning 72 out of 135 seats in the regional parliament, he said, gave “strength and legitimacy” to the campaign. As long as a deal can be thrashed out between Junts pel Si and CUP, the parliament will now issue a declaration stating its intention to launch the process towards independence. The government in Barcelona may also decide to move ahead with the creation of state-like structures, for instance a Catalan foreign ministry and tax authority. “The Catalan parliament is likely to start adopting symbolic moves towards independence, thus continuing the ongoing game of chicken with Spain’s central government,” said Antonio Barroso, in a research note for Teneo, the risk consultancy. Sunday’s result gave Mr Mas no reason to abandon this plan — but it did make clear that he will have to proceed cautiously.

One obstacle is his dependence on CUP. The other is the fact that the independence camp fell short of winning a 50 per cent majority of votes — handing its adversaries in Madrid and Barcelona a strong argument to resist the push for secession. Catalan hopes that the election would send a clear signal to the rest of Europe, and so encourage outside mediation, are also likely to be disappointed. Until the Spanish general election in December, which may or may not bring about a change in attitude towards Catalonia, there will be no fundamental change in the dynamics of the conflict.

Tobias Buck

Fonte: FT

sexta-feira, 25 de setembro de 2015

‘Pink tide’ on turn as Latin American revolutions fade

Fifty-three years ago, a Soviet ship, the Poltava, berthed in Cuba with a cargo of ballistic missiles. So began the Cuban missile crisis — a Caribbean stand-off that almost led to global conflagration.

At about the same time, 1,500 miles away in Colombia, a young communist guerrilla leader named Manuel Marulanda, better known as Tirofijo (or Sure-shot), set up base in a valley south of Bogotá. For decades, Tirofijo waged a guerrilla war on the Colombian state that eventually cost 220,000 lives. The conflict also contributed to a multibillion-dollar global cocaine trade

Back then, as in the Middle East today, it was hard to imagine a moment when these two related developments in Latin America might reach their natural end. Their revolutions — which inspired or helped finance other conflicts, from Africa to Northern Ireland — were just getting under way.

Half a century later, that historical arc is closing. Cuba is shedding its socialist model and has begun a process of rapprochement with the US. As for Colombia, the government this week made a breakthrough in peace talks with Tirofijo’s Marxist guerrillas that, in six months, could end the western hemisphere’s oldest conflict.

These are momentous events, with regional geopolitical implications that could help untie a horrendous Gordian knot of violence, migration, drug-trafficking and instability that has plagued the Americas for over half a century. At least, that is the hope.

Havana’s detente with Washington has already changed the political tone in Latin America — assisted by the Colombia peace talks — removing a rhetorical stick that revolutionary types such as President Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela have brandished against the evil empire of the north.

The same is true for other Latin American groups that called on the legacy of Cuba’s revolution to justify their own bankrupt or outdated ideologies, such as Brazil’s ruling Workers’ Party, which is embroiled in the country’s biggest-ever corruption scandal. As it rumbles on, threatening President Dilma Rousseff, that scandal is emphasising another big recent regional development — a rise in the rule of law.

In Brazil, almost for the first time, the rich and powerful, from businessmen to politicians, are being held to account.

In a different way, the same is true in Colombia, where rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) agreed this week to submit to a legal process from a state whose laws they never recognised. Along with other human rights abusers, they will submit to “transitional justice” courts.

The Farc’s demobilisation could also help diminish the flows of cocaine that run east through South America into Africa and up to Europe, now on a par with the US as leading cocaine consumers.

These hopeful events are part of a slow but tangible process of political realignment that is not so much the end of history as its next chapter. The developments are also taking place as the relative economic standing of the US improves in the region, while that of China and its state-led model of capitalism (handmaiden to so much corruption) falls.

Furthermore, the China-inspired commodity price boom that financed much of the “pink tide” of leftist governments in Latin America over the past 15 years is ending. Painfully, this will sap economic growth. But it will also expose the faultlines of much populist rhetoric and policymaking.

One example is Argentina, where President Cristina Fernández will step down after the forthcoming presidential elections, ending another era.

One cannot become too glassy-eyed. There will be reversals along the way, especially in Colombia and Cuba. The exercise of forgiveness is always hard, however much Pope Francis called for a “Revolution of Tenderness” in Cuba this week. Still, they are watershed events. And, at a time when so much of the world is plagued by conflict and forced migration, they can be celebrated as such, too.

John Paul Rathbone

Fonte: FT

quinta-feira, 24 de setembro de 2015

Andrew Chestnut: What to Expect When You’re Expecting the Pope

One of the most notable pieces of Catholic ecclesiastical garb is the triangular bejeweled hat, known as a mitre, that has been worn by popes, cardinals, and bishops to commemorate special services or ceremonies since the Middle Ages. Over the years, mitres (from the Greekmitra, or headband) have varied in type, design, and levels of embellishment.

Depending on the occasion, Pope Francis wears several different mitres, of varying ornamentation and style. But this pope, who follows in the Peronist tradition of trying to play to every political stripe, also wears several figurative hats.

On his just completed trip to Cuba, Pope Francis donned the figurative mitres of pope of the periphery, pope of the people, and evangelist-in-chief. Which hat or hats has he chosen for his maiden visit to the United States? Since no one mitre would suit all occasions on U.S. soil, expect the Argentine pontiff to wear several, as he travels to Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and New York this week.

As the pope of mercy, he will likely call on the United States and Europe to welcome refugees from Syria and elsewhere. And though it’s not on his official schedule, he will likely visit victims of sexual abuse at the hands of the church, one of the few weak points of his papacy. Donning his mitre of pope of the periphery, he will probably urge Congress to lift the trade embargo against Cuba, a policy the Vatican has been advocating for many years. And just as in Cuba, and everywhere he has gone, the magnetic Francis will put on his pope of the people cap, as he basks in the affection of adoring crowds who will turn out in impressive numbers to see him.

There is no doubt, however, that Francis will most prominently sport the hat of evangelist-in-chief of the world’s largest Christian denomination, which boasts some 1.2 billion members. So far, there is no evidence of a “Francis effect” in terms of increased attendance at mass or an increased membership in the U.S. church. A successful visit could very well translate into more positive numbers.

Even before visiting the United States for the first time, the charismatic Pope Francis had assumed the mitre of evangelist-in-chief in preparation for his historic visit. Evangelism is a daunting task in a world rife with competition from religious and secular rivals alike. Well aware of the challenges set before him on the trip, Francis has wisely chosen to focus the church’s evangelization efforts on the millions of lapsed Catholics around the world — but especially those in the Americas.

The American church is of vital importance to the Vatican, both because of its size and its recent decline. With 51 million members, the U.S. church is the fourth-largest in the world, behind Brazil, Mexico, and the Philippines. Until now it had held its own against mainline Protestants, who have suffered their own catastrophic declines in recent years. The latest surveyfrom Pew Research Center, however, shows unprecedented drop-offs for Catholics, with the percentage of the Catholic population falling from 24 to 21 percent between 2007 and 2014; one in 10 adult Americans is a former Catholic.

Francis believes the ecclesial rules and procedures on matters of the family, such as divorce, have alienated and excluded millions of Catholics. The announcement on the eve of his U.S. trip of new streamlined measures for securing annulments of marriages and a one-year pardon for those who seek forgiveness for having procured an abortion is part of his overarching goal of creating a more inclusive church.

But those same gestures have also troubled conservative bishops in the United States. Pope Francis’s lack of emphasis on the global stage of the church’s traditional messages on abortion, homosexuality, and contraception has alienated many conservative U.S. bishops, who, along with certain pundits and politicians, constitute the core of a rising conservative backlash against him.

The Catholic Church’s dwindling membership in the United States also stems from the recent drop in Mexican emigration. While Mexicans are no longer uniformly Catholic, the influx of millions of Mexican immigrants to the U.S. church had been one of the major reasons Catholicism had managed to avoid the hemorrhaging suffered by mainline Protestantism in recent decades. With both Indian and Chinese immigrants now surpassing Mexicans, the church can no longer bank on a significant future influx of new members from south of the border. For a church that is already 38 percent Latino, a long-term downturn in Mexican immigration to the United States could have dire consequences. Thus, look for the evangelist-in-chief to put immigrants and, to a lesser extent, refugees front and center during his sojourn in the United States.

The concerns Latino Catholics have with the pope are also reflected in the church’s controversial upcoming canonization of 18th-century Spanish friar Junípero Serra, the founder of many of the first missions in present-day California. Referring to Serra as “one of the founding fathers of the United States,” the Latin American pontiff fast-tracked the controversial Franciscan for sainthood, seemingly so that he could officiate Serra’s canonization in Washington’s Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception on Sept. 23.

Many Native Americans (and others), by stark contrast, view Serra as the poster boy for European religious and political colonialism, which culminated in genocide. Coming on the heels of Pope Francis’s historicapology in Bolivia this summer for the church’s role in the abuse of indigenous peoples during the Iberian conquest and colonization, his seeming lack of sensitivity to Native Americans, the one sector of the American population that has defected from Catholicism in droves, in favor of surging Pentecostalism, is decidedly peculiar. His failure to grasp the bigger picture — the massive continental exodus of indigenous populations from the church — suggests a rare instance of papal myopia.

A new Washington Post-ABC News poll shows a whopping 89 percent of American Catholics approve of the direction that the Argentine pope has led the church over the past two-and-half years. The unpredictability of this incomparable pope has itself become predictable, but there is no doubt that during his visit to the United States his most visible hat will be that of evangelist-in-chief. How smartly he wears it in Washington, Philadelphia, and New York could have a major impact on the future of the American church.

Andrew Chestnut

Fonte: Foreign policy

quarta-feira, 23 de setembro de 2015

John Gapper: Volkswagen’s deception is a warning to every company

The most dangerous three-word phrase in business is: “Everyone does it.”

However conventional it is to bend the industry’s regulations, however great an advantage your rivals gain, however much pressure you face to do so too, there is a simple test for deciding whether to succumb to temptation. What would happen if the world found out? How great would the damage be?

Volkswagen’s installation of software to make its diesel cars emit more pollution on the road than in official tests is a disaster that has forced the resignation of Martin Winterkorn, chief executive. It could tarnish the entire European auto industry, which has invested heavily in diesel technology. But it is hardly the first time that a vehicle manufacturer has behaved sneakily.

It has become so common to game European fuel efficiency tests with tricks such as taping up doors and overinflating tyres to curb drag that most diesel cars are less fuel-efficient and environmentally friendly than claimed. In the US, Ford was found to have fitted an illegal “defeat device” — the charge facing VW — to vans in 1997, and Hyundai and Kia were fined $100m last year for fixing their tests.

The car industry is not alone in such behaviour. The same thing happens in many industries, from banking to pharmaceuticals. A few companies decide gently to bend the rules and stretch regulations and others soon follow. They know it is a little dodgy but it becomes normal practice and regulators turn a blind eye. Then, one day, someone goes too far and scandal erupts.

“Although I was operating within a system . . . in which it was commonplace, I was someone who was a serial offender,” Tom Hayes, the former UBS banker jailed for 14 years last month for rigging Libor benchmark rates, told the UK Serious Fraud Office. Mr Hayes was talented at it and at enlisting other traders to co-operate. An official investigation eventually ensued.

When the backlash comes, it comes with a vengeance. Suddenly, behaviour that was common practice, passed over with a nod and a wink, or secretly condoned to keep up with rivals, is judged to be improper and perhaps illegal. “Everyone did it” is no defence. Once it has been exposed to public gaze, and regulators have been shamed for failing to stop it, there is no forgiveness.

Amid an angry search for who was responsible within a company, senior executives are hastily drilled to face official inquiries and media briefings and answer the question: “Why did you do it?” There is no good response to it, although Michael Horn, VW’s US chief executive, had an accurate one: “We have totally screwed up.”

The key to getting away with bending rules is that it needs to be done subtly and discreetly. Abuse may be common but it cannot become too blatant, or it will alert regulators that tolerate some grey areas. The car industry is a prime example: it was public knowledge that the gap between the official fuel economy data and actual performance was wide but VW stupidly took the deception to a higher level.

Frauds often start in laboratories, where the outcome is bound to be artificial. A certificate attesting that a product works a certain way in a company’s laboratory — even if no one has cheated — cannot guarantee the same of its real-world performance. Inevitably, companies tend to focus on hitting the laboratory targets they are set, just as students cram for examinations.

The gap between a well-designed test and reality need not be huge. But bright minds will soon work out how to arbitrage the two, just as banks calculated how to meet regulatory capital standards with the minimum amount of equity capital in the run-up to the 2008 crisis. Hyundai and Kia cherry-picked the best mileage tests, achieved with a following wind and special tyres.

Crowd psychology rapidly takes hold. Company X knows what Company Y is doing to game its results without being punished by the regulator, and realises it cannot compete if it does not do the same. The tests are officially sanctioned, after all, and customers are not likely to question them. Any executive or engineer who tries to resist is overruled as naive or difficult.

Rivalry creates evermore ambitious attempts to gain an advantage, and greater reputational risk. VW contrived to fit its rule-breaking gadget to 11m cars under the noses of regulators before it was discovered. Even researchers at the International Council on Clean Transportation, which identified the deception in Europe, did not believe that it would be so blatant.

Sooner or later, one company goes too far. There is bound to be a Libor super-rigger, a VW, or a GlaxoSmithKline in China, which flouts the law to such an extent that it cannot be concealed. Many companies had paid bribes to doctors and hospitals in China, but its government was bound one day to make an example of a western company doing it so systematically.

The head of a Wall Street bank once told me the lesson he had learned from financial scandals was that ethics are absolute, not comparative. “We don’t behave as badly as our rivals” was a tempting but dangerous attitude. Many companies imperil themselves by clinging to this mantra.

Volkswagen wins the dubious honour of being the worst-behaved company in its industry, but it was a contest.

John Gapper

Fonte: FT

terça-feira, 22 de setembro de 2015

A refugee crisis that Europe cannot escape

The last thing the EU wanted to deal with was a tide of refugees. The eurozone crisis, the struggle with Russia over Ukraine and the UK’s decision to hold its referendum on membership were challenges enough. Now comes a crisis that is as fraught as it is hard to manage. Yet the EU cannot choose what it must deal with. It must deal with what is before it.

The desperate human beings landing on European shores pose daunting moral, political and practical difficulties. But a way has to be found to manage them without sacrificing the values on which modern Europe was built.

In deciding what to do, the EU must draw a distinction between refugees and immigrants. Countries have legal and moral obligations to refugees. They do not have such obligations to other immigrants. Compassion for the desperate has to be distinct from a cooler assessment of the advantages and disadvantages of immigration. It may be helpful to argue that refugees could provide economic benefits to the recipient country. In many cases, no doubt, resourceful people who so much want to enter will do just that. But that is not the reason why they should be accepted.

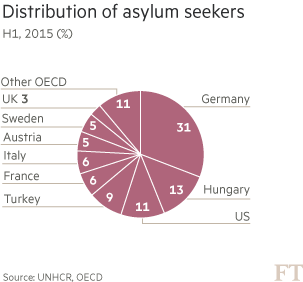

Yet persuading people to accept this distinction will be hard because the numbers have become large. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Europe will receive up to 1m asylum applications this year — an unprecedented number. Of these, between 350,000 and 450,000 are likely to be granted refugee status. Compared with previous crises, people from countries neighbouring the EU are less represented (the war in the former Yugoslavia being the cause of the spike in asylum seekers in the early 1990s), while those from further away are more so. The origin of the flows is diverse: in the first half of 2015, Syrians, Afghanis, Iraqis and Eritreans accounted for 39 per cent of all asylum claims.

The number of accepted asylum seekers this year would still amount to only 0.1 per cent of the EU’s population, hardly an unmanageable figure. The numbers reaching the EU are also small relative to the total number of refugees. The number of forcibly displaced people in the world at the end of last year was 59.5m. Moreover, nearly two-thirds of the displaced remain within the borders of their own countries, while 86 per cent of all refugees are in developing countries. Turkey hosts at least 1.7m, Lebanon 1.3m and Jordan 1m. Given the size and prosperity of the EU, the task it faces is relatively trivial,

This is not to belittle the challenges. Given the instability in the Middle East and Africa, the numbers of bona fide refugees are likely to rise. Moreover, the EU seems to have lost control over its borders. Thus, many more refugees, as well as many with a less justified claim to that status, are surely still to arrive.

So how should Europeans and their allies, particularly the US, respond?

In the short run, incomers need to be processed. Germany has stated that it expects to receive 800,000 asylum-seekers, or 1 per cent of the population, this year — the largest number ever recorded in a member of the OECD. But its decision to do so is causing huge stresses inside the EU. Jean-Claude Juncker, the commission president, has proposed that refugees be shared out among the member states. EU ministers did vote on Tuesday to relocate 120,00 people across the continent over the next two years. But members differ greatly in their true willingness to take refugees. In any case, once inside the border-free Schengen area, people cannot be tied down. They will move wherever they expect the best lives. The EU needs a common policy, at least for the Schengen area. The UK and US also need to take more refugees.

The same sort of solidarity is needed for another task: helping refugees integrate successfully. This is going to be difficult and costly. They will need assistance with learning the language and housing. Richer countries will have to assist the less well off ones. A revitalised European economy would also help.

Solidarity is also needed to help overstretched countries on the frontiers, notably Greece and Italy. It is hard to see how the border-free Europe of today will be maintained without a well-resourced border protection and immigration service. But this requires common policies: a daunting political task.

Another need is to provide the vulnerable states on the front lines of the refugee crisis with far more assistance. This applies, in particular, to those bordering Syria. A particular moral burden rests on countries whose irresponsibility helped destabilise much of the Middle East — the US and the UK foremost among them. But France shares responsibility for intervening in Libya and then walking away. At the least, these countries need to help those living with the results of their actions.

Now come two really hard tasks. The first is to bring a measure of stability to destabilised countries. For Europeans, the most important are Syria, Iraq and Libya. And, similarly, Europeans need at least to try to halt the people-smuggling at source. This will require a combination of diplomacy and coercion. If Europeans are unable to muster much of this, they will remain at the mercy of events. The US must also play a more effective role as a producer of order, not disorder, than it has at least since 2001.

Europeans just want to be left alone. But the EU lives in a world of chaos. It needs to find a way to cope, other than by becoming a fortress that lets the desperate perish on its defences. It needs a comprehensive and effective strategy. Yes, this time pigs do have to fly.

Martin Wolf

Fonte: FT

segunda-feira, 21 de setembro de 2015

Sweetness of Mint economies still entices

There was a time when countries all over the world aspired to be one of the Brics. The acronym comprised Brazil, Russia, India, China (later adding South Africa). These countries seemed to embody the economic dynamism and promise of the world’s emerging markets.

So there was plenty of investor interest when, in 2014, Jim O’Neill — the former chief economist at Goldman Sachs and the man who had coined the term Brics — began to champion the economic prospects of another group of countries: the Mint economies.

For this select group of four — Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey — it was clearly a blessing to be marketed as the next big thing.

Many investors thought the Mints sounded simply delicious. This was another group of four countries with the characteristics that defined the original Brics: large populations, strong growth rates, rapidly emerging middle classes and entrepreneurial cultures.

The past 18 months, however, have been disillusioning for fans of both the Brics and the Mints. Brazil, South Africa and Russia are in the middle of economic crises and China is growing at its slowest pace for a generation.

The Mints also seem troubled. The problems in each of the four countries involved are quite specific. However, in broad terms, they tend to include political instability and slowing economic growth. Investors who were once all too happy to ignore the structural problems of these emerging markets can now see little else.

Inevitably, the picture is mixed and there is some good news out there as well. Nigeria, in particular, can point to its successful presidential election earlier this year. This saw the first peaceful transition of power following an election from one head of state to another in the 55 years since Nigeria’s declaration of independence.

Better still, the new president, Muhammadu Buhari, seems to be genuinely committed to tackling the endemic corruption that has held Nigeria back for decades.

Nonetheless, in the short term, the country faces several formidable economic and political challenges. The fall in the oil price has slashed Nigeria’s export earnings and government revenues.

Nigeria must also cope with Boko Haram, the extremist Islamist insurgency that has claimed about 20,000 lives and created 1.5m refugees. The new government seems to be taking the fight to Boko Haram with renewed energy, but it will be a long struggle.

Some of the problems facing Nigeria are present in the other Mints. The falling oil price is a problem for both Mexico and Indonesia, both of which are large exporters. Islamist militancy has been a problem in Indonesia in the past, although things are relatively quiet for the moment.

Turkey, however, is suffering badly from the conflict in neighbouring Syria. The prolonged civil war there has created millions of refugees, some 2m of whom are now in Turkey.

The old grievances between the Turkish state and the Kurdish militants of the PKK have also flared again into violent conflict. And the general atmosphere of political uncertainty has been further fostered by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s decision to go for fresh elections on November 1, as he struggles to secure the parliamentary majority he would need to change the constitution and bolster the powers of the presidency.

For a decade after 2003, when Mr Erdogan came to power, Turkey enjoyed strong and non-inflationary economic growth. That boosted the Turkish leader’s reputation for competence and allowed investors to ignore some of his more eccentric views — such as his oft-stated belief that there is an international “interest rate lobby” that is agitating for Turkey to have inappropriately high borrowing costs.

In the current economic environment, however, Turkey needs competent economic management that inspires international confidence. Inflation is at about 8 per cent, unemployment is at 11.3 per cent, and the country is running a large current-account deficit of about 6 per cent of GDP. It looks vulnerable to capital flight.

The problems these four countries face include political instability and slowing economic growth

Political leadership is also now an issue in both Mexico and Indonesia. When President Enrique Peña Nieto first came to power in 2012, he was hailed both at home and abroad as a charismatic and dynamic leader.

Over the past year, however, the Mexican leader has had what the Queen of England might have described as an annus horribilis. His administration has been hit by corruption scandals, slowing growth, a stalling economy, and public outrage over a mass killing of students and the escape from jail of one of the country’s leading drug lords.

As a result, opinion polls suggest that the president is now Mexico’s least popular for some 40 years.

One spark of hope, however, is that stronger growth north of the border might spur demand for Mexican goods. The country may also continue to benefit from rising labour costs in China, which makes Mexico look like an appealing base for manufacturers wanting to export to the US.

The troubles of the Chinese economy are more of a threat to Indonesia. As a country in the Asia-Pacific region and a major exporter of commodities, Indonesia has benefited from many years of strong Chinese growth.

With China slowing, Indonesia needs imaginative and confident leadership. So it is unfortunate that the current president Joko Widodo is increasingly being portrayed as ineffectual and diffident.

More broadly, all the Mints are now suffering from the fact that investors across the world are cooling on “emerging markets”.

But while classification as an emerging market might not be regarded as a strong selling point at the moment, the factors that have driven emerging-market success over the past two generations have not disappeared.

In the medium term, therefore, globalisation, expanding international trade, relatively low labour costs and a rising middle class are once again likely to prove a potent combination.

Gideon Rachman

Fonte: FT

Assinar:

Comentários (Atom)