The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) caused a splash last weekend with anannual report that spelled out in detail why it disagrees with central elements of the strategy currently being adopted by its members, the major national central banks. On Wednesday, Fed Chair Janet Yellen mounted a strident defence of that strategy in her speech on “Monetary Policy and Financial Stability”. She could have been speaking for any of the major four central banks, all of which are adopting basically the same approach [1].

Rarely will followers of macro-economics have a better opportunity to compare and contrast the two distinct intellectual strands in the subject, as explained in real time by active policy makers. Faced with exactly the same set of evidence, the difference in interpretation is stark, as is the chasm between them on monetary and fiscal policy.

Martin Wolf has already done a superb job in dissecting the BIS report. To a large extent, the dispute can be viewed as old wine in new bottles: the “Wicksellian” BIS versus the “Keynesian” Yellen [2]. But the Great Financial Crash has provided the two schools with plenty of new evidence to deploy.

Let us start with a few similarities between them. There is agreement that financial crashes that trigger “balance sheet recessions” lead to deeper and longer recessions than occur in a normal business cycle. There is also agreement that inflation is not likely to re-appear any time soon, and that the current recovery should be used to strengthen the balance sheets of the financial sector through regulatory and macro-prudential policy. That, however, is where the agreement ends.

The roots of disagreement can be traced back to the causes of the GFC. The BIS views the crash as the culmination of successive economic cycles during which the central banks adopted an asymmetric policy stance, easing monetary policy substantially during downturns, while tightening only modestly during recoveries (ie the Greenspan and Bernanke “puts”).

On this view, monetary policy has been too easy on average, leading to a long term upward trend in debt and risky financial investments. The financial cycle, which extends over much longer periods than the usual business cycle in output and inflation, eventually peaked in 2008. But, even now, the BIS says that the central banks are attempting to validate the long term rise in debt and leverage, instead of allowing it to correct itself. Excessive debt, it contends, is preventing the rise in capital investment needed for a healthy recovery. Financial and household balance sheets need to be repaired (ie debt needs to be reduced) before this can take place.

In contrast, the mainstream central bank view denies that monetary policy has been biased towards accommodation over the long term. Ms Yellen’s speech claims that higher interest rates in the mid 2000s would have done little to prevent the housing and financial bubble from developing. She certainly admits that mistakes were made, but they were in the regulatory sphere, where there was insufficient understanding of the new financial instruments that would eventually exacerbate the effects of the housing crash. Higher interest rates, she says, would have led to much worse unemployment, without doing much to reduce leverage and dangerous financial innovation.

This difference in interpretation of the past leads to a major difference in view about today’s monetary policy. The BIS argues that zero interest rates and quantitative easing are becoming increasingly ineffective in boosting GDP growth. Instead, they are artificially inflating asset prices, and blocking a necessary correction in excessive debt. Macro-prudential and regulatory policy might be helpful here, but will not be sufficient. The main risk is that the exit from these accommodative monetary policies may come too late.

The Yellen view is in sharp contrast to this. There is no admission that quantitative easing is becoming ineffective, or that excessive debt should be reversed [3]. There is an outright rejection of the view that interest rates have been too low throughout previous cycles. If anything, the “secular stagnation” argument is adopted, suggesting that real interest rates have been and remain too high, because the zero lower bound prevents them from falling as far as would be required to reach the equilibrium real rate. On this view, the danger is that the exit from accommodative monetary policies will come too early, not too late.

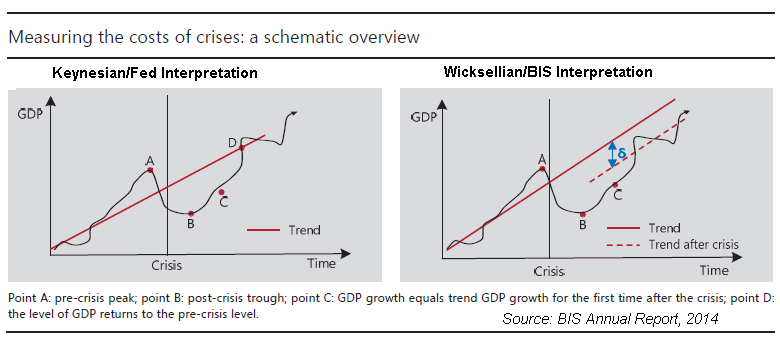

There are many other differences on top of this. The BIS argues that there has been a permanent loss of capacity in the developed economies following the GFC, illustrated in the graphs below. This is due to forbearance on bad loans by the banking sector, which allows moribund companies and technologies to survive, while failing to finance the next wave of productive innovation. The mainstream view, by contrast, is that there has been a temporary loss of capacity, but that this can eventually be restored, if demand recovers sufficiently. Ms Yellen’s belief that labour participation rates can rebound is a case in point.

This divergence of views on economic capacity leads in turn to a major difference on appropriate fiscal policy. The BIS implies that cyclically-adjusted fiscal policy is looser than it seems, because GDP can never return to its earlier trends. The Keynesian/Yellen view is that fiscal policy should not be tightened too soon, and perhaps not at all until output has fully recovered.

Finally, the two views are far apart on the need for international co-operation in the setting of monetary policy. The BIS says that this is essential, because the effects of easy monetary policy are felt far beyond national borders, leading to a risk of currency wars and protectionism. It sharply criticises the “own-house-in-order doctrine” followed by all of the major central banks.

Conclusion

The main purpose of this blog has not been to adjudicate between the two alternative approaches, though regular readers will know that my own view is usually fairly close to the Fed/Yellen mainstream. It has been to emphasise just how different the current central bank orthodoxy is from another, internally coherent, interpretation of the past. Claudio Borio and his colleagues at the BIS have done macro-economics a service by spelling out the policy implications of their Wicksellian framework so clearly.

Paul Krugman correctly points out that the BIS has been wrong in the past about the threat of inflation. Furthermore, their supply-led analysis of the real economy probably underestimates the pervasive importance of demand shocks during most economic cycles (see Mark Thoma). But the risk of financial instability is another matter entirely. It is optimistic to believe that macro-prudential policy alone will be able to handle this threat. The contrasting needs of the real economy and the financial sector present a very real dilemma for monetary policy.

The BIS was right about the dangers of risky financial behaviour prior to the crash. That caused the greatest demand shock for a century. Keynesians, including the Chair of the Federal Reserve, should be more ready to recognise that the same could happen again.

——————————————————————————————-

Footnotes

[1] See, for example, Andy Haldane’s recent remarks at the Camp Alphaville conference.

[2] Actually, both New Keynesian models, and Wicksellian models, recognise the concept of the “equilibrium” real interest rate. One shorthand way of describing the recent differences between the two approaches is that the BIS thinks that the central banks have persistently set the actual real rate below the Wicksellian equilibrium, while the Keynesians tend to believe the opposite. A good discussion of the concept of the equilibrium rate in the two approaches appears in this 2011 BIS paper by Claudio Borio and Piti Disyatat.

[3] At least part of the long term rise in debt is viewed by many Keynesians as a natural and sustainable part of economic development, and not as a chronic problem that needs to be corrected.

Gavyn Davies

Fonte: FT