The extraordinary volatility in all financial asset classes in the past week can only be described as ominous. On Wednesday, the US ten year treasury, perhaps the most liquid financial instrument in the world, traded at yields of 2.21 per cent and 1.86 per cent within a matter of hours. This type of volatility in the ultimate “risk free” asset has previously been seen only in 2008 and other extreme meltdowns, so it clearly cannot be swept under the carpet.

A few weeks ago, investors had widely expected a strengthening US economy to lead to a rising dollar and a tighter Federal Reserve, with an amazing 100 per cent of economists saying they were bearish about bonds in a Bloomberg survey in April. Instead the markets have started to act as if the world is about to topple into recession, and an abrupt reversal of speculative positions has probably led to exaggerated market moves, in both directions.

Now that excessively large positions have been washed out, what is the underlying message from the past month of market action?

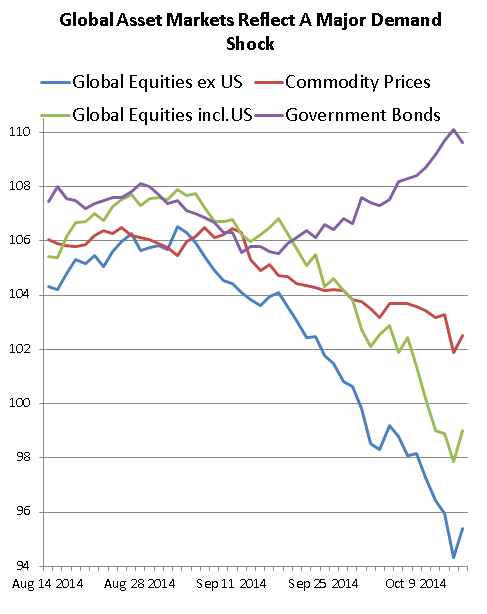

The first graph shows very clearly that the major asset classes have all moved in a classic “risk off” direction, consistent with a contractionary demand shock in the global economy – equities are down, especially outside the US, bonds are up, and commodities are down. Credit spreads have widened, including sovereign bond spreads in the euro area. Within the equity markets, cyclical stocks have under-performed, while defensives have done relatively well.

The first graph shows very clearly that the major asset classes have all moved in a classic “risk off” direction, consistent with a contractionary demand shock in the global economy – equities are down, especially outside the US, bonds are up, and commodities are down. Credit spreads have widened, including sovereign bond spreads in the euro area. Within the equity markets, cyclical stocks have under-performed, while defensives have done relatively well.

So it all seems very straightforward. Surely there must have been a sudden deterioration in economic activity. After all, the German economy has slowed markedly, taking the euro area down with it. Recent data surprises must have been adverse.

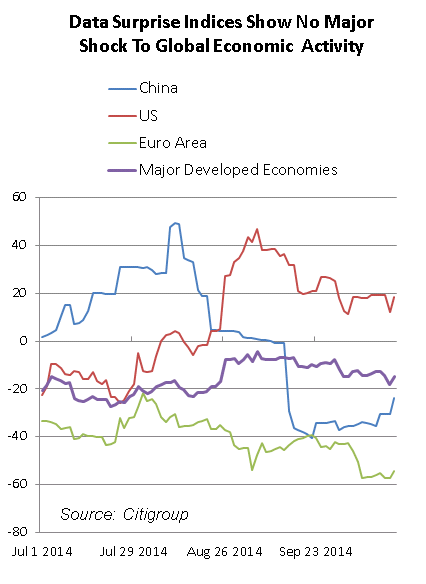

Well, no, actually. There have been downward revisions to GDP forecasts in the euro area, but these have been offset by slight upward revisions in the US and recently even in China. The latest nowcasts for global activity have remained firm, and data surprises in the world as a whole have been close to flat for several months (see graph and more details here).

Well, no, actually. There have been downward revisions to GDP forecasts in the euro area, but these have been offset by slight upward revisions in the US and recently even in China. The latest nowcasts for global activity have remained firm, and data surprises in the world as a whole have been close to flat for several months (see graph and more details here).

Maybe the slowdown in the euro area has increased the perceived risk of recessions returning to other parts of the world, but there has been no general downward revision to central projections for global GDP. In fact, J.P. Morgan’s team of economists, which tracks global activity data extremely carefully, said on Friday that signs of above trend global GDP growth were beginning to emerge. Markets have clearly been out of synch with the flow of information in this regard.

What there has been, however, is a marked drop in inflation expectations built into the bond market right across the world. This has also been led by the euro area, where inflation expectations in the inflation swap market have started to challenge the ECB’s promise to keep inflation “below but close to 2 per cent”.

Mr Draghi has said on many occasions that he will adjust monetary policy as necessary to ensure that medium term inflation expectations are in line with the ECB’s target, but investors have become hugely sceptical about this. Unless the ECB is able to alter this perception drastically in the near future, the progressive “Japanification” of the euro area could become hard to reverse.

Mr Draghi has said on many occasions that he will adjust monetary policy as necessary to ensure that medium term inflation expectations are in line with the ECB’s target, but investors have become hugely sceptical about this. Unless the ECB is able to alter this perception drastically in the near future, the progressive “Japanification” of the euro area could become hard to reverse.

So surely that must be it – declining inflation expectations, driven from events in the euro area, must have increased fears of debt deflation on a global basis.

It is hard to deny that this factor has been important. But there is also a much more benign reason for the widespread drop in inflation expectations, and that is the 25 per cent decline in oil prices since last June. Since this has been triggered largely by an increase in oil supply, it will act like a positive supply shock to oil importing economies.

In a low inflation environment, some economists may perceive even this as a bad development, since it could raise real interest rates, and may make it more difficult to service debt (see David Wessel) . But in any oil importing nation, the economy as a whole will be much better off as less resources are used to pay for oil imports, so the overall scope to service debt will improve. As long as inflation expectations remain fixed (which looks very doubtful in the euro area, but not elsewhere), the oil shock should be beneficial.

When oil prices fell sharply in 2009, global inflation went negative for a while, but inflation expectations remained stable at about 2 per cent, and no damage was done to the economic recovery. This time, real GDP is likely to benefit by about 0.5 to 1.0 per cent as a result of the oil supply shock.

Overall, then, three separate factors have probably been at work:

- a reversal of speculative positions, which has had temporary effects on asset prices;

- a contractionary and deflationary demand shock in the euro area;

- an oil shock that will also be deflationary, but will be expansionary for many economies.

The combined effects of all this should be unequivocally supportive for bonds, but ambiguous or even supportive for some global equity markets.

What am I missing? One concern is that the markets are beginning to recognise that secular stagnation may be gripping the world economy (see Robert Shiller). If so, the recent risk sell-off might have been reflecting a decline in medium term GDP growth expectations throughout the global economy. But once again this fails to show up in any recent change in consensus GDP forecasts.

Another possibility is that the market shock will itself tighten monetary conditions sufficiently to cause a slowdown in global growth, as happened in previous euro crises. But the financial system seems more robust this time, and has not shown any sign yet of increased stress.

Finally, the markets may be starting to doubt whether the central banks actually have the weapons needed to stop global deflationary forces in their tracks. Robin Harding reminds us that Ben Bernanke once said, wisely, that quantitative easing “works in practice but not in theory”. The implication is that it only works because it shifts inflation and other economic expectations in the desired direction.

If markets start to doubt this, they have entered much more dangerous waters. But the relief rally on Friday, triggered by the merest hints that central banks may consider further asset purchases, suggests that we are not there yet.

Gavyn Davies

Fonte: FT