quarta-feira, 23 de dezembro de 2015

Indonesia’s silent history of slaughter

The National Museum of Indonesia is packed with ceramics, maps and schoolchildren. When I visit, in search of information on the mass killings of 50 years ago, the director looks visibly put out.

“Why are you writing about 1965?” Intan Mardiana asks. The museum covers pre-19th century history, she explains, not politics. “People here don’t know much about that.”

Following a failed coup blamed on the Communist party of Indonesia (PKI), more than half a million people were killed between late 1965 and early 1966, part of a purge that targeted the ethnic Chinese, trade unionists and left-leaning artists as well as PKI members.

Co-ordinated by the military and local vigilante groups, the killings ushered in three decades of dictatorship by General Suharto. Half a century later, there is still little by way of acknowledgment, let alone retribution, in the nation that is now the world’s third-largest democracy.

Ms Mardiana directs me to another museum dedicated to the late General Abdul Nasution, who having survived the 1965 coup led the fight to suppress communism.

I venture into the musty, deserted house where he had lived. There is no ticket office and no one else to be seen. A guard finally emerges in the living room, with its bright yellow walls and floral sofa, and hands me a leaflet that relates in Indonesian the story of the PKI’s raid on Nasution’s home, during which his daughter was killed. There was nothing about the mass murders that followed.

Since the fall of Suharto in 1998, freedom of speech has improved dramatically but debate about the killings still seems to take place mainly overseas. I learnt about them when I moved to Jakarta this year. A former correspondent recommended The Act of Killing , Joshua Oppenheimer’s 2014 Oscar-nominated documentary, in which men who took part in the executions re-enact their crimes. “When I approached them, I found that within minutes of meeting me they would launch into boasts of how they killed,” the director explains via Skype. Many of the perpetrators remain powerful in their communities, he says.

The violence of the film forms a striking contrast to the image of gentle Javanese culture and Balinese spirituality. Along with The Look of Silence, a sequel, it has triggered international debate. But in Indonesia the documentaries — like the killings — are not widely discussed. Instead, the government has grown moresuspicious of foreign journalists and wary that this year’s anniversary could raise fresh questions.

Officials dismissed the International People’s Tribunal that met in November in The Hague to shed light on the slaughter. In the city of Yogyakarta, a cultural centre in western Indonesia, officials have confiscated toys bearing Communist symbols and talks on 1965 were banned at this year’s Ubud Writers and Readers Festival. “I think they were just panicking,” says Janet DeNeefe, festival organiser.

When President Joko Widodo swept to power last year, the first leader from outside the political and military elite, some hoped he would improve freedom of speech. These expectations were misguided, local friends tell me. Mr Widodo, who campaigned as a man of the people, is considered to share the views of those reluctant to revisit the wrongs of the past. The killings laid the foundations for Suharto’s rule, and schools have long presented 1965 as the defeat of a political faction that threatened the nation’s future.

With foreigners raking over this violent past and chastising the government, some Indonesians are understandably prickly. One local historian started his testimony to The Hague tribunal with a disclaimer: “I am not here to make my country and people look bad.”

Ariel Heryanto, an academic at the Australian National University, says the silence is the result of official repression. “How many globally connected young people know about the Santa Cruz, Soweto, Khmer Rouge or Tiananmen Square killings?” he asks. “Young Germans feel sick of the national obsession with guilt and the endless discussion on the Holocaust.”

Yet in Berlin, for example, there is no shortage of museums and lectures for those who want to know more.

Avantika Chilkoti

Fonte: FT

terça-feira, 22 de dezembro de 2015

Hope and fear in the endless Greek crisis

The Greek economic crisis has blighted the country and the eurozone for six years. The election last January, which brought Alexis Tsipras and his leftwing Syriza party to power, added further friction between Greece and the rest of the eurozone. Mr Tsipras vowed to undo austerity — a promise he could not deliver on his own.

In the event, after winning a referendum in July against the terms offered by the eurozone, he agreed to a new €86bn three-year eurozone programme on terms not so different from those he had persuaded the Greek people to reject. After a split in his party, Mr Tsipras then won another election in September. Yet the capital controls imposed in June remain in force and the economy has fallen back into recession.

Is there a good chance that economic recovery will take hold in 2016? This was in my mind as I visited Athens last week. My conclusion was that a chance does exist. But it is not, alas, that good.

The starting point has to be with the differences of view among the main players: the Greek government and wider political community; the International Monetary Fund; and eurozone creditors, particularly Germany.

As Mr Tsipras made clear last week, one of his aims is to avoid another programme with the IMF. He finds its demands hard to bear. More broadly, he thinks that “the sooner we get away from the [bailout] programme the better for our country”. He notes: “If Greece completes the first [progress] review in January, we’ll be covering more than 70 per cent of fiscal and financial measures in the agreement.” He hopes Greece will soon regain its sovereignty or, with the IMF out of the picture, at least will only have other Europeans to deal with.

The Athens government is also optimistic about the economic future. Mr Tsipras expects remaining capital controls to be lifted by March 2016 and for Greece to regain access to international capital markets by the end of the year. Banks have been recapitalised more cheaply than feared and confidence in the banking sector is returning. The government also hopes economic growth will soon resume. (See charts.)

Nevertheless, the government is hoping for further debt relief. The IMF agrees with it. This is also plausible. Interest due on public debt is forecast by the Bank of Greece to jump from 2 per cent of gross domestic product up to 2021 to over 8 per cent in 2022 and then stay over 4 per cent until the 2040s. Sustainability largely depends on the terms of the new debt. If the eurozone made it possible for Greece to borrow on triple-A terms forever, the debt would be sustainable. Otherwise, it probably would not be.

The IMF argues that Greek debt has become unsustainable only because the government failed to meet its commitments. That is doubtful. The ability of Greece to deliver was never credible. Moreover, while the IMF does support Greece on debt relief, it is very sceptical of its ability to deliver structural reforms in the absence of a political consensus that the reforms are desirable. It insists, against the government, that the country is well behind where it was a year ago on reforms. It has backtracked in important areas.

A sizeable primary fiscal deficit (before interest payments) is also likely next year. A particular bugbear for the IMF is unsustainably generous spending on pensions. The government says cutting pensions further is impossible. The IMF responds that the fiscal transfers to the pension fund of 9 per cent of GDP and the huge cuts to discretionary spending are unsustainable.

Eurozone creditors disagree with the IMF on the need for more debt relief. But Germany at least very much wants the IMF to remain a lender. So great is German mistrust of this (or indeed any) Greek government and the European Commission that it wants IMF-style conditionality imposed on Greece more or less indefinitely. But both the Greek government and the staff of the IMF dislike this possibility. The former hates it because it wants a free hand. The latter hate it because they fear the conditions for successful programmes do not exist. This being so, they cannot, in good conscience, recommend one to the board.

Far too many obstacles to smooth progress now exist: review of the eurozone programme due early next year; expiry of the IMF programme in March; the fragility of the economy and, more broadly, lack of confidence and trust inside Greece and between it and the creditors. With exit currently ruled out by both sides and a strong political consensus in Greece that a way must be found to stay inside the eurozone, these frictions should be manageable. But this is definitely not a case of living happily ever after. This is a bad marriage in which the two main partners agree only that divorce would be worse (albeit only just) and the counsellor seeks a way to abandon the quarrelsome couple.

So how might this mess end? One possibility is that enough of the reform package is enacted and enough of a post-crisis economic bounceback arrives to convince the Greek government to stick with reforms, thereby generating a virtuous circle of reform and growth. Another is that the programme fails once again, because the economy itself fails. The government (which has a tiny majority) then falls, to be replaced by a pro-reform and more successful government. Yet another possibility is that a successful government does not arrive and Greece ultimately leaves the euro.

This is for the longer term. Soon, however, decisions have to be made, including by the IMF. In the background to these lie political disarray in Spain, discontent in Italy and the migrant crisis, on which Greece is on the front line.

I looked up to the Parthenon. It is old, damaged and under repair. Yet I hope it will stand for further millennia. Europe, too, is old, damaged and under repair. I hope Greece will prosper inside a stable eurozone. Yes, it is still mostly hope.

Martin Wolf

Fonte: FT

sexta-feira, 18 de dezembro de 2015

Boa sorte Ministro Nelson Barbosa.

Nelson Barbosa é um ótimo economista, mas acho que sua escolha foi mais um erro da Presidenta Dilma. Na atual conjuntura, seria recomendável um político acompanhado de uma boa equipe de economistas. Deu certo no governo Itamar com FHC e no Lula com Palocci.

Desejo ao Nelson Barbosa sucesso e toda sorte do mundo. Que Deus lhe ilumine nesta dificil tarefa.

Desejo ao Nelson Barbosa sucesso e toda sorte do mundo. Que Deus lhe ilumine nesta dificil tarefa.

quinta-feira, 17 de dezembro de 2015

Abandonar o ajuste fiscal é um tiro no pé...

Dia histórico no STF: vitoria da lógica e do bom senso. Não tenho formação na área juridica, meus pitacos tem como fundamento as minhas parcas leituras em filosofia analitica, que me levam a crer que havia algo de errado no parecer apresentado ontem por um Ministro do STF. Alias, é possível inferir, a partir do que se fale e ouve, por estas bandas, que a filosofia analítica ainda continua sendo pouco conhecida no grande bananão. Enfim, o fato é que, aparentemente, ainda não nos transformamos em uma banana republic. Ainda, caros eternas polianas.

O Valor já demitiu tantas vezes o pobre do Levy que é dificil levar a serio qualquer noticia em relação a sua saida. Nem por isto a esquerda burra, como mencionado no post de ontem, deixar de soltar rojões. Imagino que contam com orgasmo total da velha canção do Arrigo Barnabe: a escolha do Nelson Barbosa ou alguem da mesma linha para a cadeira do Levy, acompanhada de rejeição do ajuste fiscal. Doideira total. Eu sei, mas esperado, em se tratando de analfabetos em teoria econômica. Nem falo da teoria econômica mainstream, mas do trabalho de bons economistas heterodoxos.

Abandonar o ajuste fiscal é um tiro no pé, remover o Levy é um erro, mas se inevitável, um politico com uma boa assessoria econômica seria uma boa idéia. Foi a opção do Itamar e do Lula e o resultado foi bem melhor que o esperado pelo mais otimista de plantão.

quarta-feira, 16 de dezembro de 2015

Banana Republic

A perda do grau de investimento era uma cronica de morte anunciada. De quem é a culpa? De todos, naturalmente, mas a maior parte deve ser debitada na conta da DilmaI, que afinal, pariu o problema. A oposição ao fazer tudo que estava ao seu alcance pra sabotar o ajuste fiscal, pra não falar da recusa em aceitar o resultado das eleições, é responsável pelo agravamento do cenario político, com forte impacto sobre o econômico. Em outras palavras, a chamada classe política, é a grande responsavel pela opera bufa em que estamos.

A turma que causa um serio estrago na imagem e reputação dos raros heterodoxos que são ótimos economistas, deve estar soltando rojões para comemorar a segunda perda do grau de investimentos. Imaginam que com esse resultado Levy será derrubado e o seu posto ocupado por um bravo heterodoxo que não domina os rudimentos da teoria econômica. Confesso que não tenho a imaginação necessaria para vislumbrar qual seria a alternativa desta banda nefasta dos heterodoxos. Mas, duvido que o resultado seja menos desastroso que o produzido pela famigerada nova matriz econômica.

Estava precificado e alem do mais, no atual cenário de instabilidade política é refresco perto do que poderá acontecer, a depender do que será decidido pelo STF. Será que estamos condenados a ser uma República de Bananas?

terça-feira, 15 de dezembro de 2015

There is no money behind the fiscal tree

Russell Long, the southern Democrat who was long-serving chair of the US Senate finance committee, composed the ditty “Don’t Tax You, Don’t Tax Me, Tax the Fellow Behind that Tree”. His point was that, when politicians explain that public budgets will be balanced without pain through the elimination of waste or an assault on tax avoidance, you know they are not serious. There is plenty of waste and avoidance — but if eliminating them was painless, it would have happened.

Researcher Maya Forstater has done valuable service in puncturing the extravagant claims of campaigners that the lives of the poorest people could be transformed by money from behind the tree. Some of these arguments are simply laughable. Christian Aid, a charity, has claimed the import of 66m refrigerators to Spain from China in 2007 at an average cost of 38 cents represents a shift of €8bn out of China (through trade mispricing). According to the Christian Aid report: “The money lost could be used to provide schools, hospitals and better living conditions worldwide.” I have always tried to teach students that the most likely explanation of a startling statistic is that it is wrong: but, it seems, to no avail. There are only 18m households in all Spain.

ussell Long, the southern Democrat who was long-serving chair of the US Senate finance committee, composed the ditty “Don’t Tax You, Don’t Tax Me, Tax the Fellow Behind that Tree”. His point was that, when politicians explain that public budgets will be balanced without pain through the elimination of waste or an assault on tax avoidance, you know they are not serious. There is plenty of waste and avoidance — but if eliminating them was painless, it would have happened.

Researcher Maya Forstater has done valuable service in puncturing the extravagant claims of campaigners that the lives of the poorest people could be transformed by money from behind the tree. Some of these arguments are simply laughable. Christian Aid, a charity, has claimed the import of 66m refrigerators to Spain from China in 2007 at an average cost of 38 cents represents a shift of €8bn out of China (through trade mispricing). According to the Christian Aid report: “The money lost could be used to provide schools, hospitals and better living conditions worldwide.” I have always tried to teach students that the most likely explanation of a startling statistic is that it is wrong: but, it seems, to no avail. There are only 18m households in all Spain.

But the fantasy of Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the opposition Labour party, that austerity could be avoided by money currently behind the tree is indeed a fantasy. Calculations of the scale of tax avoidance and evasion — like estimates of “tax expenditures” from reliefs and allowances — assume that, in all other respects, behaviour would remain unchanged if tax that is currently avoided or evaded were collected. It would not. Many relevant transactions would not occur at all. It is an open question how much additional company tax could actually be collected by poor countries without discouraging the external investment essential to their development.

But one need not believe in pots of gold behind the tree to be concerned about tax avoidance. More thoughtful tax campaigners — and the UK’s HM Revenue & Customs — have defined avoidance as a situation where most reasonable people would agree that, if the facts are as described, tax should payable whether or not it is legally payable.

Tax is thus a moral issue. Not because we should take pleasure in paying tax but because the behaviour of well off people, and large companies, should conform to the expectations of most reasonable people. It is not just the rule of law but also a sense of shared values that makes economic and social life possible in the modern state. That is why multinational businesses should not engage in transactions without commercial substance; and why celebrities faced with large tax bills as a result of failed avoidance schemes deserve what they get.

John Kay

Fonte: FT

domingo, 13 de dezembro de 2015

sexta-feira, 11 de dezembro de 2015

Deva vu

É dezembro, diz um amigo. Ele tem razão. Fosse Agosto, o mês das tragedias politicas no grande bananão, ficaria mais fácil entender a situação de deja vu desse final de ano. FHC, da mesma escola de política do grande lider da direita brasileira( o velho PCB pró sovietico), Carlos Lacerda, reencena o mesmo papel, que sua falta de carisma e eterno ar professoral, transforma em exercicio da mais pura canastrice. É um ator sem talento, que jamais seria salvo por um bom texto e tão pouco por um diretor talentoso.

Ele não esta sozinho neste bizarro loop temporal. Temer, o eterno canastrão de filme mexicano -ou seria de filmes B das matines dos tempos d'antanho? - faz o papel que na versão original pertenceu a ao Cafe Filho. A sua carta é um exercicio do mais puro machismo anos 50: daquele tempo em que a mulher era sempre a culpada pela traição. Ela me obrigou, era a desculpa padrão. Deverás, deverás....

A maligna UDN dos liberais de orelha de livro, renasce das cinzas liderada - quem diria - pelos antigos comunistas pro sovieticos do PCB. Mui democratas, como sabemos, mestres na arte de conspirar contra a democracia: mudaram de lado, mas velhos habitos são dificeis de perder: o cachimbo deixa a boca torta, já alertava meu saudoso pai.

Nesta opera bufa, aquele que poderia ser o digno representante de uma direita democratica que tanta falta faz a nossa democracia, optou pelo silêncio tumular. Não confia no próprio taco? Logo, ele, o favorito pra levar a faixa em 2018... Mas ao que parece um picole de chuchu está fadado ao rodapé da historia culinaria do país.

Enquanto escrevo, capisbaixo, pela tragica situação do país, observo a deslumbrante florada da lagrima de Cristo do meu jardim, os filhotes da sabia nos galhos do jardim manga, sinais que a vida continua e que é bela, apesar da tempestade criada pelos trairas que nada aprenderam no tempo que passaram no exilio....

Dr. Strangelove do Bixiga

É surpreendente que depois do longo período de trevas que deixou como um dos legados vários mortos sem sepultura, alguem possa sair em defesa de um plano econômico que, para ser implementando, requer a quebra da legalidade. Mais surpreendente, ainda, quando o seu autor é diretor de uma instituição jovem, mas irmã de outra que, em SP, acolheu alguns intelectuais perseguidos pela ditadura militar e garantiu a liberdade de atuação do movimento estudantil em sua sede.

Triste sem dúvida, mas é bom deixar claro que sua posição tem nome e sobrenome: apoio a um golpe de Estado. Sim, Golpe. Impedimento, como argumentei em outro post não é necessariamente golpe. Mas, impedimento sem provas é golpe. Não chama-lo pelo nome, não é nem um pouco surpreendente, em se tratando do país conhecido pela sua criatividade no uso da linguagem para, por ex, acobertar o racismo de cor e de origem.

A política econômica deve ser pensada a partir do respeito a legalidade, ou seja, ela não pode ter como primeira medida a quebra da democracia e a incineração da constituição pela qual tantos lutaram. Fato esse, desconhecido por vários economistas que se dizem liberais. Não é o caso, do infeliz, autor do artigo, que nunca afirmou ser um liberal, mas um fiel discípulo( erudito, diga se de passagem) do famoso barbudo. Mas, confesso, que acho que ele tem mais afinidade com o Dr. Strangelove. Taí um bom nome pra ele: Dr. Strangelove do Bixiga.

quarta-feira, 9 de dezembro de 2015

The fiction of a unified, harmonised Asean

If you think European nations are having a hard time holding it together — strained by disputes over immigration, austerity and debt — spare a thought for the 10 countries that form the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

True, compared with Europe, they face few fatally divisive problems. Most of Southeast Asia is contending with the impact of a slowing China and braced for the turbulence that could accompany the steady normalisation of US monetary policy. Yet there are no big financial transfers within Asean, a loose federation akin to the EU of the 1950s. No country is threatening to leave, nor are there fundamental differences over the direction of policy.

Still, as Asean prepares for an important milestone this month — the creation of a theoretically single market — it is worth reflecting on the incredible diversity of the “new bloc on the block”.

The 625m people of Asean live in states that range from the sprawling Indonesian archipelago of 250m souls to the tiny sultanate of Brunei, with 400,000. You have Singapore, with a gross domestic product per capita of $55,000, and Cambodia at just over $1,000. There are cacophonous, if imperfect, democracies (Indonesia, the Philippines); Communist dictatorships (Vietnam); and military juntas (Thailand). There are states with majority Muslim populations, such as Malaysia and Indonesia; ones that are mostly Buddhist, including Myanmar; and the predominantly Roman Catholic Philippines. Asean countries are even split over which side of the road to drive on. In five of them it is the left, and five the right — although in Vietnam they drive on both.

Given this diversity, it is no small miracle that Asean is forging ahead with integration by creating the Asean Economic Community, which formally takes effect on December 31. Theoretically, this creates a unified market in goods and services, and clears the path to free movement of people and harmonisation of regulations. It should be no surprise that much of this is fiction.

Although 95 per cent of tariff lines are at zero, non-tariff barriers, from diverging regulatory standards to dysfunctional ports, make trade between nations frustratingly hard. Nor is there anything like free movement of labour, even in the skilled sector, which is supposedly on its way to full liberalisation. Multinationals operating in Asean complain that it is often hard to transfer staff from one country to another. Meanwhile, millions of unskilled migrants, from construction workers to fishermen, flit between countries in the shadows. In the penumbra of regulation, there is flagrant violation of human rights and even outright trafficking.

Asean has no ability to sanction countries that flout its rules. It is “all carrot and no stick”, Jayant Menon, an expert on trade integration at the Asian Development Bank, told a Financial Times conference on the subject recently. Asean has a skeleton secretariat, to put it kindly, based in Jakarta. It has a budget of $17m — not enough to get an EU commissioner out of bed in the morning. Asked who you call when you want to call Asean, Abdul Farid Alias, president of Maybank, a Malaysian bank that has a presence in every Asean country, responds curtly: “No one.”

In spite of such flaws, some companies are trying to treat Asean as a single market. General Motors and GlaxoSmithKline have made Singapore their regional hub, though that may be because of the ease of doing business in the city state rather the attractions of Asean. Others are seeking to build production centres in Indonesia, Thailand or the Philippines. Rising wages in China are making these and other countries, including Myanmar and Cambodia for textiles, and Vietnam for textiles and electronics, more attractive. Diageo, the drinks group, has placed hefty bets on Asean — lured, says Sam Fischer, its regional president, by consistent growth, young populations and the prospect of an expanding urban middle class. Yet it has sometimes been disappointed, such as when Indonesia suddenly clamped down on alcohol sales this year. Above all, says Mr Fischer, foreign investors want Asean to enforce clear and consistent rules.

That may be a problem. The “Asean way” favours consensus. Its lack of overarching ambition is a strength as well as a weakness. By taking a softly softly approach over the nearly five decades since it was founded, Asean has avoided pooled sovereignty and a single currency, both of which have become so contentious in Europe. It has held its project together with remarkably little friction. It has scored quiet successes, from steady tariff reduction to nudging Myanmar back into the fold of respectable nations.

Yet carrots and consensus can only take you so far. Those looking for a new but faster-growing Europe in the heart of Asia will be disappointed.

David Pilling

Fonte: FT

terça-feira, 8 de dezembro de 2015

Medidas econômicas e construção do bem comum

Artigo que escrevi, no inicio de Novembro, para a pagina de opinião do jornal O São Paulo. Acredito que ele ainda continua atual. Não acredito que os eventos recentes na esfera política altera a analise e medidas propostas. Ainda acredito na solidez das instituições da Republica e que a democracia e a constituição não serão jogadas no lixo neste momento de grave crise institucional. Impedimendo com provas não é golpe, mas sem elas é golpe. Em 1999 fui contra o impedimento do Presidente Fernando Henrique Cardoso por que não havia provas contra ele e pelo mesmo motivo sou contra o impedimento da Presidenta Dilma.

Um ano após as eleições que a reconduziram ao cargo de Presidente da República, Dilma Rousseff ainda continua encontrando enormes dificuldades para aprovar no Congresso Nacional as medidas necessárias para corrigir o péssimo legado econômico do desenvolvimentismo populista do seu primeiro mandato.

A fragilidade política e a aparente falta de convicção em relação a urgência de um forte ajuste fiscal levou à decisão, infeliz, de apresentar uma proposta orçamentária para 2016 com déficit primário, que foi fundamental na decisão da agência de classificação de risco Standard & Poor's de retirar o grau de investimento do País. Assustado com a possibilidade das outras duas agências risco adotarem a mesma posição, que teria graves consequências para nossa já combalida economia, o Governo Dilma, reapresentou uma nova proposta de orçamento com medidas de ajuste fiscal focado em aumento da receita.

Esta estratégia de ajuste fiscal, segundo a literatura especializada, não é, no entanto, a mais recomendável. O corte de despesas ainda que, politicamente difícil, seria a melhor opção. Os cortes de gastos implicam em menor impacto sobre a produção, ou seja, tem um efeito recessivo menor, em razão da retomada do investimento privado, que é o grande responsável pelo crescimento econômico em uma economia de mercado.

Infelizmente, em razão da enorme fragilidade política da atual administração, a opção politicamente mais viável acaba sendo mesmo o aumento de impostos, posto que o foco do ajuste fiscal, no curto prazo, deve ser a geração de um superávit primário, que dificilmente será suficiente para a estabilização e ou redução da dívida pública como proporção do PIB, mas que deverá ser o suficiente para demonstrar o compromisso da atual administração com o equilíbrio fiscal durante o seu mandato.

O retorno da Contribuição Provisória sobre Movimentação Financeira (CPMF) é a melhor solução, se comparado à alternativa que seria o aumento do CIDE (Contribuição de Intervenção de Domínio Econômico) sobre o combustível, que teria forte impacto sobre a inflação. Outras medidas, como é o caso do retorno do Imposto de Renda para lucros e dividendos distribuídos e maior esforço na cobrança de devedores da dívida ativa da União, não eliminam a necessidade da aprovação da CPMF, mas sinalizariam um compromisso da atual administração em não colocar somente na conta da classe média e dos mais pobres o custo do ajuste fiscal.

As medidas propostas na peça orçamentária para 2016, no entanto, não atacam o problema do déficit estrutural que requer medidas de longo prazo, que passam, necessariamente, por uma discussão, mais ampla, sobre o modelo de sociedade que desejamos construir. Reconhecer a existência de um desequilíbrio estrutural entre receitas e despesas, causado pela expansão do gasto social, não implica (como sugerido por alguns analistas) em um novo pacto social com a exclusão de vários direitos, que atingiria fortemente a população mais pobre.

É fundamental frisar que não há saídas magicas para atual situação econômica que, apesar de grave, nem de longe se aproxima das terríveis crises dos anos 80. Para superá-la é preciso lembrar que a pior coisa é aquela que é pior para todos e que o objetivo do agir político deve ser sempre o bem comum. O país tem instituições sólidas e saberá superar a situação atual com a retomada, sustentada, sem populismo, do crescimento econômico com justiça social. Este é e sempre será um grande desafio, que deve ser assumido por todos os brasileiros.

Fonte: O São Paulo, edição 3077, 11 a 17 de Novembro de 2015

segunda-feira, 7 de dezembro de 2015

France needs a better way to unseat its ruling clique

The National Front has emerged as the big winner in France’s regional elections. By the time the second round is over on Sunday, it will probably have claimed victory in at least two regions. Whether it does or not, having secured almost 30 per cent of the vote, it has become the country’s largest political party.

For the first time since 1945, therefore, the extreme-right has become mainstream. This poses a challenge for everyone else in politics — Social Democrats, Conservatives and the liberal right.

The FN is very far from being a French version of the Dutch Freedom party or the UK Independence party. Its xenophobia is far more extreme. The party promotes an agenda of ethnic discrimination that, if implemented, would result in internal strife along ethnic and religious lines. Its dysfunctional economics would produce a recession. And it would give rise to tremendous difficulties between France and the rest of the world.

This is the reason why, putting all ideological divisions aside, the Socialist party has asked its candidates to withdraw from the second ballot in every region in which the FN stands a chance of winning.

The least the Republicans could have done was to reciprocate. By staying in the race, France’s main Conservative party has squandered the chance to ensure that the FN is defeated.

What do the FN’s gains tell us about the political situation of France? Undeniably, it reveals the existence of a large and growing constituency who want no more of the alternation between centre-right and centre-left. Instead, they want to unseat all the incumbents. The appeal of this party is that it speaks in words they can understand and promises to return the country to “the people”.

If that seems like a flimsy reason for entrusting the powers of the state to a party that has no experience whatsoever of running it, consider that the French political elite is an ageing one, whose leaders have been at the helm for three or even four decades. Because few people enter politics from the corporate world or from other walks of life, it is an incestuous scene.

There is a French tradition that high-ranking civil servants, most of them educated at a single elite school, the École nationale d’administration, are the dominant force in the main political parties. As much as an endorsement of a particular set of policies, a vote for the FN is a signal of discontentment with this political elite.

The FN is different. It gives career opportunities to candidates from all walks of life — blue-collar workers, young urban professionals, middle-class women. It is this openness — rather than the FN’s disastrous policies — that the parties of the centre should seek to emulate. As many as 80 per cent of French people say they do not trust parliament or the political parties. Restoring that trust is the only way we can avoid a total collapse of the democratic system.

Beyond that, the conservative right must refine its ideology and come up with a strategy that will lessen the appeal of the FN. The Republican party encompasses many ideological shades — everything from social conservatism to anti-EU nationalism to economic liberalism. This latter tradition, however, is losing ground.

Nicolas Sarkozy, the former president, tried to please both wings of his heterogenous party. But it did not work. Criticising the Schengen agreements, which have removed passport checks at many intra-EU borders, was not enough to win back voters from the FN. Neither were his rhetorical claims that France had lost its soul by giving up to foreign influences. Yet both alienated the centre-right and singing the praise of free-market economics did not undo the damage.

Defeating the extreme right will take more than fancy presentation. It requires a new political offer. This probably means the Republicans have to disappear altogether, so that a single but divided party can be replaced by two distinct families of the right.

One of them would be committed to more European integration, free-market economics and a multicultural society.

The other would stand for an illiberal democracy of the kind the FN favours, in which the majority imposes its will on smaller groups and keeps France out of globalisation.

Separating these two strands of conservative ideology would give the first, more outward-looking version a chance to flourish — and deprive the second, insular version of its chance to bring the decline of France to a point of no return.

Jean-Yves Camus is an associate researcher at

the French Institute for International and Strategic Affairs

Fonte: FT

quinta-feira, 3 de dezembro de 2015

How history answers Syria’s unholy war

The Middle East reminds us that there is nothing so unholy as a holy war. Europe learnt this in the 17th century. Confessional competition between Catholicism and Protestantism fused with temporal rivalry to provoke the Thirty Years’ War among the continent’s leading powers.

The fighting, bloodier than any previously seen, ended when raison d’état triumphed over theology. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 marked the end of Europe’s great wars of religion. This should tell us something about the present conflict in Syria.

he wholesale slaughter that followed could not have been imagined in 1618, when mainly Protestant Bohemia rose up against the Catholic Holy Roman Empire. The subsequent wars — there were several — drew in Habsburg Spain and Austria, France, the Netherlands, Sweden, Poland, Russia, Denmark and the big German principalities. England, Scotland, the Ottoman Empire and Russia all claimed walk-on parts.

The fighting was mostly on German soil, but the battles were between armies of foreign mercenaries. As befits wars conducted in the name of God, cruelty and brutality were endemic. By many accounts, the population of Germany was cut by a third or more. Torture and mass burnings of alleged witches were commonplace.

For Catholic and Protestant, read Shia and Sunni. There are, I am sure, a hundred differences between the horrors that engulfed Europe and the flames consuming Syria. There are also uncomfortable coincidences. The brutality flowing from the intertwining of the spiritual and territorial is one; the misfortune of a patch of ground — Germany then, Syria now — in becoming a battlefield for outside powers is another.

The Thirty Years’ War began as an assertion of independence by the Protestant princes of Bohemia and Germany against the Catholic Holy Roman Empire. But it was also about France’s fear of encirclement by the Habsburgs of Spain and Austria, the Dutch struggle for independence from Spain, Sweden’s bid to assert itself, Poland’s eclipse and Denmark’s last throw as a big power. Half-a-dozen other states also claimed a vital national interest in the outcome.

Confessional loyalties were sometimes elbowed aside by secular ambitions. Thus Catholic France joined up with Protestant Sweden against its co-religionists in Spain and Austria — just, perhaps, as Shia Iran now finds advantage in allying itself with Sunni Hamas. Protestant Denmark fought at different moments on either side of the confessional divide. Competing Lutherans and Calvinists sometimes questioned whether Rome was the real enemy.

By 1648, the wars had recast the geopolitical balance. France emerged a victor, the Holy Roman Empire a loser. Westphalia became a foundation for the modern European state. If there was a thread running through the various treaties that settled the territorial disputes it was that the confessional choices of states should no longer be a casus belli. Today’s Middle East, with the same combustible mix of theological and earthly rivalry, is a long way from reaching such an understanding.

One way of looking at the fighting in Syria is an uprising of the majority Sunni against the Alawite, or quasi-Shia, regime of Bashar-al Assad. This is the obverse, you could say, of what happened in Iraq: the fanatics of the self-styled Islamic State have prospered with the support of Iraqi Sunnis dispossessed by the toppling of Saddam Hussein.

The dividing lines on the ground are important. But, as in 17th-century Europe, what has kept the fires burning has been the involvement of outside powers. Syria has become the arena for the long-simmering regional contest between (Sunni) Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies on one side, and (Shia) Iran on the other. Russia sees a vital national interest in sustaining the regime in Damascus; Turkey in overthrowing it.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkish president, talks about the enemies of Mr Assad as his “Sunni brothers”. But the shooting down of a Russian jet by Turkish warplanes patrolling the Syrian border has little to do with rival versions of Islam. Ankara’s fear is the emergence of a powerful Kurdish entity in northern Syria and Iraq — a concern that explains its dangerous ambivalence towards Isis. Russia, like the US and Europe, sees Isis as a serious threat, but does not want to risk losing its Mediterranean naval base.

For Tehran, the preservation of the Assad regime is part of a strategy that has seen Iran push its influence deep into the Arab world. Saudi Arabia and the Gulf monarchies want to counter what they fear is Iranian encirclement. These Sunni states also want to see Isis defeated, but not at the price of a victory for Tehran. And here are just a few of the dizzying complexities of the conflict.

For the US and its allies, the overarching interest is the re-establishment of regional stability and the defeat of the Isis jihadis. But this is a conflict that defies partial solutions. An eventual peace will demand the unravelling of the confessional and the temporal — that religion surrenders to realpolitik.

The Gordian knot is the struggle between Iran and Saudi Arabia, but a settlement would have also to acknowledge Russia’s interests and Turkey’s fears. Impossible, many will say. Maybe. But until it happens, today’s Syria will live the horrors of 17th-century Germany; and Isis will continue to find a safe haven for its twisted credo.

Philip Stephens

Fonte: FT

quarta-feira, 2 de dezembro de 2015

India’s headline GDP growth disguises problems below the surface

So it is official. India is the only Bric left standing. Brazil, which shrank 4.5 per cent year on year in the third quarter, seems destined for its worst recession since the 1930s. Russia’s oil-dependent economy is in the grip of fierce contraction and South Africa has only just managed to avoid outright recession. Even the mighty China, after years of stimulus and over-reliance on ozone-destroying heavy industry, is growing at its slowest pace in 25 years.

That leaves India alone among the once-vaunted Brics nations putting up a decent show. Official data this week show that its economy grew 7.4 per cent in the third quarter from a year earlier, accelerating from 7 per cent in the previous three months. The performance, driven by fixed capital investment and industrial production, was more impressive still given that output from farming, which employs about half India’s workforce, is limping along at 2.2 per cent. On the face of it, there is much growth to be had simply by shifting some of those farm labourers into more productive sectors. In short, the world’s third-largest economy in purchasing power parity terms can now legitimately lay claim to be the global economy’s most impressive outperformer.

Indeed, much is going right for India. Even before Narendra Modi swept to power last year in a blaze of optimism, its economic fundamentals were improving. Low oil prices are a boon: they have helped repair a current account position that once put the country among the most vulnerable to US Federal Reserve-induced capital outflows. Its growth is less dependent on exports than that of many developing economies, with 70 per cent of gross domestic product driven by consumption.

In Raghuram Rajan, its central bank governor, it has a figure akin to Paul Volcker, the former Fed chairman, in his determination to control inflation, a phenomenon that is particularly damaging to the hundreds of millions of India’s poor. Steady improvement on that front means India now has the room to lower interest rates: they have already come down 1.25 percentage points this year.

Nor can the “Modi effect” be discounted. Although some of the shine of the prime minister’s election victory has been wiped off by subsequent defeats — most recently in the state of Bihar — India has a greater sense of purpose than it did in the final lacklustre years of Manmohan Singh’s administration. Mr Modi has ramped up spending on infrastructure and taken credible steps to deal with the legacy of rampant corruption in the auction of government assets from coal to telecoms spectrum.

It would be wrong, however, to take continued outperformance for granted. That is what countries such as Brazil and Russia did — and look where they are now. India has many problems bubbling beneath the surface, from bad debts in the banking system to a worrying reluctance of entrepreneurs to invest in their own, seemingly successful, economy. Most of the rise in investment has been government-led.

There are at least three reasons not to count India’s chickens just yet. First is the slow pace of reform. Despite all his vim and vigour, Mr Modi has found it hard to push his agenda through Delhi’s political process. Because of a hostile upper house, almost nothing of import was passed in the last parliamentary session. Optimists say the wily prime minister will get the better of the system yet. One hope is that he will spark competition between states implementing, say, the most attractive land reform as they vie for investment. Many hope that one more push will result in the enactment of a much-delayed goods and services tax. Reform of restrictive labour laws, which will hobble Mr Modi’s ambition to make India a manufacturing hub, has not even been discussed.

Nor is it clear whether the GDP numbers can be taken at face value. A rebasing exercise means that the 7.4 per cent headline figure is almost certainly flattering. The outwardly robust performance is hard to square with other data such as weak corporate earnings, slow motorcycle sales and subdued loan growth.

Finally, even if we believe the numbers, headline GDP growth is not everything. Of course, poor countries need to grow fast if they are to tackle poverty. Yet, unless they lay the foundations for development — not only through appropriate reforms but also through investments in health and education — that growth can quickly peter out. India lags behind its peers in measures of health, literacy and its record on improving the position of women. None of this bodes well for a country where, courtesy of a youthful population, almost one in five of all global jobs must be created in the next several decades.

For the moment, India is a standout. But as the fading fortunes of its fellow Brics demonstrate, that is no guarantee of future success.

David Pilling

Fonte: FT

terça-feira, 1 de dezembro de 2015

Understanding the new global oil economy

Why have oil prices fallen? Is this a temporary phenomenon or does it reflect a structural shift in global oil markets? If it is structural, it will have significant implications for the world economy, geopolitics and our ability to manage climate change.

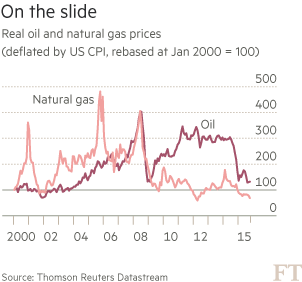

With US consumer prices as deflator, real prices fell by more than half between June 2014 and October 2015. In the latter month, real oil prices were 17 per cent lower than their average since 1970, though they were well above levels in the early 1970s and between 1986 and the early 2000s. (See charts.)

A speech by Spencer Dale, chief economist of BP (and former chief economist of the Bank of England) sheds light on what is driving oil prices. He argues that people tend to believe that oil is an exhaustible resource whose price is likely to rise over time, that demand and supply curves for oil are steep (technically, “inelastic”), that oil flows predominantly to western countries and that Opec is willing to stabilise the market. Much of this conventional wisdom about oil is, he argues, false.

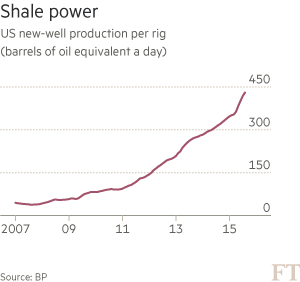

A part of what is shaking these assumptions is the US shale revolution. From virtually nothing in 2010, US shale oil production has risen to around 4.5m barrels a day. Most shale oil is, suggests Mr Dale, profitable at between $50 and $60 a barrel.

Moreover, the productivity of shale oil production (measured as initial production per rig) rose at over 30 per cent a year between 2007 and 2014. Above all, the rapid growth in shale oil production was the decisive factor in the collapse in the price of crude last year: US oil production on its own increased by almost twice the expansion in demand. It is simply the supply, stupid.

What might this imply?

One implication is that the short-term elasticity of supply of oil is higher than it used to be. A relatively high proportion of the costs of shale oil production is variable because the investment is quick and yields a quick return. As a result, supply is more responsive to price than it is for conventional oil, which has high fixed costs and relatively low variable costs.

This relatively high elasticity of supply means the market should stabilise prices more effectively than in the past. But shale oil production is also more dependent on the availability of credit than is conventional oil. This adds a direct financial channel to oil supply.

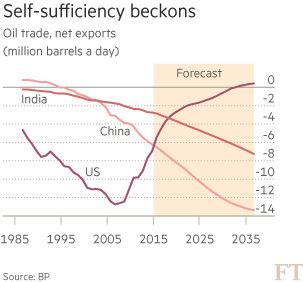

Another implication is a huge shift in the direction of trade. In particular, China and India are likely to become vastly more important net importers of oil, while US net imports shrink. Quite possibly, 60 per cent of the global increase in oil demand will come from the two Asian giants over the next 20 years.

By 2035, China is likely to import three-quarters of its oil and India almost 90 per cent. Of course, this assumes that the transport system will remain dependent on oil over this long period. If it does, it demands no great mental leap to assume that US interest in stabilising the Middle East will shrink as that of China and India rises. The geopolitical implications might be profound.

A further implication concerns the challenge for Opec in stabilising prices. In its World Energy Outlook 2015 , the International Energy Agency forecasts a price of $80 a barrel in 2020, as rising demand absorbs what it sees as a temporary excess supply. A lower oil price forecast is also considered, with prices staying close to $50 a barrel this decade.

Two assumptions underlie the latter forecast: resilient US supply and a decision by Opec producers, notably Saudi Arabia, to defend production shares (and the oil market itself). But the low-price strategy would create pain for the producers as public spending continues to exceed oil revenues for a long period. How long might this stand-off last?

A final set of implications is for climate policy. The emergence of shale oil underlines what was already fairly clear, namely, that the global supply capacity is not only enormous but expanding. Forget peak oil. As Mr Dale notes: “In very rough terms, over the past 35 years, the world has consumed around 1tn barrels of oil. Over the same period, proved oil reserves have increased by more than 1tn barrels.”

The problem is not that the world is running out of oil. It is that it has far more than it can burn while having any hope of limiting the increase in global mean temperatures over the pre-industrial levels to 2°C. Burning existing reserves of oil and gas would exceed the global carbon budget threefold. Thus, the economics of fossil fuels and of managing climate change are in direct opposition. One must give. Profound technological change might undermine the economics of fossil fuels. If not, politicians will have to do so.

This underlines the scale of the challenge leaders confront at the climate conference in Paris. But the response to the fall in oil prices shows how hopeless policymakers have been. According to the IEA, subsidies to the supply and use of fossil fuels still amounted to $493bn in 2014. True, they would have been $610bn without reforms made since 2009. So progress has been made.

But low oil prices now justify elimination of subsidies. In rich countries the opportunity of low prices could — and should — have been used to impose offsetting taxes on consumption, thereby maintaining the incentive to economise on use of fossil fuels, increasing fiscal revenue and allowing a reduction in other taxes, notably on employment. But this important opportunity has been almost entirely missed.

One has to ask whether there is the slightest chance that effective action, rather than window-dressing, will emerge from Paris. I hope to be proved wrong, But I am, alas, sceptical.

Martin Wolf

Fonte:FT

sexta-feira, 27 de novembro de 2015

Cull the grey vote — it is an affront to democracy

It was “like addressing sheeted tombstones by moonlight”, said Florence Nightingale’s friend Sidney Herbert, after speaking in the House of Lords. We should never be surprised by the things said or done in those Elysian Fields.

The latest folly from this assembly of has-beens is to conclude that the way to fix what is wrong with British politics is to allow 16-year-olds to vote. This is like looking at the photograph of St Paul’s Cathedral in the Blitz and concluding that it needed better scaffolding.

There is something intensely comical in an unelected bunch of old people opining on how extending the franchise to young people might improve our democracy. How about requiring anyone who wants to legislate to have first to undergo the indignity of standing for election?

Still, consider what the unelected worthies suggest: that 16- and 17-year-olds be allowed to vote in the referendum on whether Britain should remain in the EU. The government is against the idea because, among other things, it would require extra time to register the new voters, limiting its room for manoeuvre on the referendum date. It is not much of an argument.

Young people will have to live with the consequences of the decision long after Prime Minister David Cameron, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn and the rest of us (I am 65) have joined the celestial choir singing “Ode to Joy”. Perhaps there is an argument for letting 16-year-olds have a say. They can, after all, marry, pay taxes, claim benefits or join the army. On the other hand, we do not allow them to gamble, buy cigarettes or alcohol or to serve on a jury. The 2010 Sunbeds (Regulation) Act bans them from using tanning salons. Society cannot decide whether they are children or young adults. If they are to come of age at 16, they will have to get a grown-up to buy the booze for the party.

If 16-year-olds are to be allowed to take part in a referendum, there is no reason why they should not vote in general elections. And why stop at 16? After all, Britain has the lowest ages of criminal responsibility in Europe (10 in England and Wales, eight in Scotland, compared with 18 in Luxembourg and Belgium).

Their lordships are right: the political system favours the elderly. There are fewer than 6m people aged 18 to 24 in Britain, but more than 11m aged 65 or older. Some scarcely know what day of the week it is, yet their ballot papers are worth the same as a Cambridge professor’s. And politicians know that older people are much more likely to vote — as one put it to me privately, “there’s not much else going on in lots of their lives”.

The grey vote is the one constituency no politician dares to offend. Bus passes? Certainly. Free television licences? Of course. And the number of elderly voters grows year by year.

Pollsters say some stupid things but I am inclined to believe them when they say that in Britain young people are less excited by politics than elsewhere in Europe. One reason is the remoteness of parliament, now colonised by a curious sect who have made the getting of political office their obsessive concern. The young have other things on their minds; education, mating, music and finding somewhere to live are more important to them than to old people watching their bungalows increase in value while they moulder away inside.

At the heart of the issue is responsibility — the counterpart to rights. It is easy to see why parties like Labour and the Scottish National party believe in lowering the voting age: they think most young people will vote left. Yet these are the parties that do not trust young people to act responsibly; hence the nannying about tobacco, alcohol and sunbeds.

But are the old people, whose interests increasingly dominate politics, responsible? “No taxation without representation” are watchwords of democracy. Perhaps the formulation should be reversed — no representation without paying taxes. Why should those who no longer make a contribution to the state be allowed a disproportionate role in choosing governments, which forces others to pay the taxes to keep old people in the style to which they feel entitled? The solution is not to lower the voting age but to cap it.

More sensible to make an explicit connection between working and voting (while recognising the needs of the working-age sick and disabled and stay-at-home mothers). A decent society is one in which those responsible for compassionate actions, such as pensions or healthcare, are those who pay for them.

Members of the House of Lords are not allowed to vote in elections. They should have the vision to see that the privilege of not taking part ought to be accorded to everyone who has passed their sell-by date.

Jeremy Paxman is an FT contributing editor

quinta-feira, 26 de novembro de 2015

How not to deal with a humbled Putin

I wonder what happened to Vladimir Putin the grandmaster? I had given up counting the commentaries casting the Russian president as a daring, decisive foil to a collection of feeble, vacillating leaders in the world’s advanced democracies. The hyperbole was always just that. Now we are catching a glimpse of Russia’s real vulnerability.

By any measure, Mr Putin has lost some of his shine. Moscow’s military gambit in Syria was widely hailed as a game-changer — the sort of bold chess opening that US President Barack Obama would never risk. By committing forces the Russian leader had positioned himself at the centre of any international effort to end the civil war. He had put paid to western demands for the forced removal of Bashar al-Assad. Banished from polite diplomatic society after the invasion of Ukraine, the scowling figure in the shadows was suddenly back at the top table.

Television images of sleek Russian warplanes and submerged submarines raining fire on Syrian rebels burnished the president’s self-image as the leader of a great patriotic revival. Who said Russia was no longer a superpower? We have short memories. Not so long ago western audiences mistook missiles lighting up the sky for America’s power to bend the arc of history. Remember Baghdad in the spring of 2003?

The lionisation of Mr Putin came before terrorists affiliated to the self-styled Islamic State planted the bomb that killed nearly 220 Russian holidaymakers on a flight home from the Egyptian resort of Sharm el-Sheikh; the murders were claimed as a reprisal for Moscow’s Syrian intervention. And it was before this week’s downing by Turkish warplanes of a Russian jet, said to have strayed across the Syrian border into Turkey’s airspace. And it was before Ukrainian saboteurs — with or without the collusion of Kiev — turned off the lights in Russian-occupied Crimea by blowing up power-supply lines.

What some had imagined a victory for Mr Putin in Ukraine has turned into a mire. He can claim to have prevented that country falling under the spell of the west, though that possibility was always overstated. Annexing Crimea, though, is a costly burden. So, too, are the pro-Russian enclaves in eastern Ukraine. For their part, European governments have surprised themselves with their own resolve by sustaining economic sanctions that impose real costs on Moscow.

Even without US and European sanctions, the Russian economy would be in serious trouble. The collapse in oil and gas prices has exposed Mr Putin’s failure to modernise or diversify the nation’s sources of output. The economy is shrinking and living standards are falling. Capital flight is draining foreign reserves and overseas investors are staying away. Some say the worst is over; few expect a significant recovery.

None of this is to imply Mr Putin is under threat. At home, his assertive nationalism has public purchase. His popular support remains somewhere in the stratosphere. Mr Obama, Germany’s Angela Merkel or almost any other leader you could think of would happily swap approval ratings with the Russian president. Nor will recent setbacks diminish his capacity to make trouble, whether in Ukraine or in Syria.

The signs are that both Moscow and Ankara want to avoid escalation after the downing of the Russian jet, but it would be a mistake to rule out another flare-up. The overlapping military operations between Russia and western powers offer an ever-present risk of accidental confrontation.

So what should be the west’s next move? The first answer is that it should seek to capitalise on Mr Putin’s troubles by deepening engagement with Moscow in the quest for a ceasefire and then for some sort of a political framework for Syria. The second is that Washington, Berlin and Paris must avoid loose talk about resets and rapprochement. To borrow a phrase from the late Margaret Thatcher, this is no time to wobble. The third, following from the second, is that the west should take what the diplomats call a strictly instrumental approach to the relationship with Moscow.

The need to co-ordinate military operations in Syria speaks for itself. If Mr Putin is willing to forge a real partnership against Isis, the west should respond with encouragement. There can never be a durable settlement while Mr Assad remains in office, but the so-called moderate opposition held up in Washington and elsewhere as government-in-waiting is in large part a fiction. A political transition would require time to forge a viable alternative and the consent of both Russia and Iran.

The unforgivable mistake would be to accept any crossover from Syria to Ukraine. Mr Putin will want to trade co-operation in Syria for western concessions in Ukraine. That way lies ruin. European leaders tempted to ease sanctions should recall that they successfully separated the Iran nuclear deal from the dispute about Ukraine. And no one should forget that Russia, every bit as much as the west, has an interest in the defeat of violent Islamist extremism.

Syria has left everyone in a hole. The US and Europe misread the conflict almost from the outset. Mr Putin, the decisive tactician, has shown himself a poor strategist. If a deal is still possible then everyone should be ready to seize the moment, but no one should imagine that the Russian president has given up his revanchist worldview.

Philip Stephens

Fonte: FT

quarta-feira, 25 de novembro de 2015

Mauricio Macri will make a difference beyond Argentina

This is how socialism ends, not with a bang but with a squeaker. After a commanding lead during the run-up to Sunday’s presidential run-off election, in the end conservative challenger Mauricio Macri’s victory came down to only 200,000 votes in a nation of more than 40m. The defeat of Cristina Fernández’s political machine has prompted euphoria in much of Buenos Aires. Once it dies down, the president-elect will have his work cut out.

In democratic Argentina, non-Peronist presidents are the rarest of birds; none has finished a term in office. Mr Macri does not command a majority of Senate seats (although he can block hostile legislation). He has relatively little support among Argentina’s powerful provincial governors.

Meanwhile, much like Juan Domingo Perón, whose style shifted from militant nationalism to populist socialism, Peronism is amorphous, more patronage than ideology. It will recover.

Mr Macri may need time to transform the economic wasteland he inherits from predecessors who were happy to default on their country’s debt and shield inefficient industries from competition. But the effects of his victory may be sooner felt outside Argentina.

As the socialist tide in Latin America has receded, dragged back by the death or retirement of its charismatic leaders and the turning of the commodity cycle, it has left many a bloated government high and dry — in Brazil, Venezuela and Chile as well as Argentina. Still, Kirchnerism is the first to expire.

As the largest Hispanic country in South America, Argentina casts a sizeable shadow, and Mr Macri has promised to re-engage with the US and strengthen ties with the EU. Just as the rise of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela helped bring populist movements to power across the continent, Argentina’s choice of a market-friendly pragmatism may galvanise opposition movements elsewhere.

In Venezuela’s legislative elections next month, Mr Macri’s victory has shown a nervous electorate that real change is possible through the ballot box. There is even a remote chance it might strengthen the resolve of Brazilians seeking to impeach Dilma Rousseff, or persuade Bolivians that there can be workable alternatives, ahead of February’s referendum on scrapping term limits for Evo Morales.

Beyond what he represents, the importance of Mr Macri lies in what he can do. The past two decades has seen the proliferation of supranational organisations in South America, which has weakened US influence over the sovereign affairs of their members. This, though, has led to an erosion of values. A code of silence has prevailed as like-minded nations refused to call out one another on the chipping away of democratic protections, free media and human rights.

Nowhere is this as visible as in Venezuela, now governed by Nicolás Maduro, a gaffe-prone Pierrot who succeeded Mr Chávez and displays a penchant for collecting political prisoners. Mr Maduro is the most visible symptom of the region’s troubling slide towards authoritarianism.

Mr Macri invited Lilian Tintori, the wife of jailed Venezuelan opposition leader Leopoldo López, to his victory speech. He has promised to invoke a “democracy clause” and suspend Venezuela from the Mercosur trade bloc during a summit in Paraguay, days after he takes office. The odds are stacked against success. All but one of Mercosur’s other voting members are allied with Mr Maduro, and Brazil has already made its opposition to suspension clear. Still, standing up to Mr Maduro would be worth it. It is the one promise that Mr Macri can deliver unilaterally. Forcing the conversation would signal to the US and the EU that Mr Macri is the future, and that the future is bright.

Daniel Lansberg-Rodriguez teaches Latin American business at the Kellogg School of Management

segunda-feira, 23 de novembro de 2015

Mauricio Macri’s choice for Argentina: shock treatment or gradual change

The election of Mauricio Macri on Sunday as Argentina’s new president marks the end of an era for the country and, indeed, for the region as a whole. The bounty that accompanied the commodity boom of the past 12 years is over; leaner times will require more prudent and orthodox economic management. That is as true of the economic populism that characterised the two administrations of Cristina Fernández, Argentina’s outgoing president, as it is of other South American countries with out-of-favour leftist governments, such as in Brazil.

There will also be less populist grandstanding of the sort that Ms Fernández is known for. The centre-right Mr Macri, the son of a wealthy businessman and currently the mayor of Buenos Aires, is certainly a business-like figure. In addition, the commodity price crash has cut down to size the popular appeal of charismatic leaders, such as Ms Fernández, who modelled herself on Evita Perón.

The failures of her populist model, and a widespread weariness with her sharp-tongued and confrontational style, saw to that. The same is true of other recent political movements in South America, such as Chavismo in Venezuela, Lulismo in Brazil and perhaps Evo Morales’ rule in Bolivia. South America’s so-called “pink tide” is receding.

Still, Mr Macri’s electoral success last night is unusual. He promised change; indeed, his coalition is called “Let’s Change”. That promise helped propel him from a supposedly distant second in the polls just a month ago, to victory last night with 51.4 per cent of the vote. But change to what, exactly; in which areas; and, how?

The economy is the most pressing issue that Mr Macri must address. Inflation is running at double-digits, foreign reserves have collapsed, there are currency controls, the exchange rate is overvalued, the government is shut out of international markets by its long-running court case with holdout creditors, the central bank is printing money to finance the fiscal deficit and the domestic economy suffers from a web of domestic distortions — including energy subsidies that can shrink a household’s monthly energy bills to the price of a cup of coffee.

The hard call that Mr Macri must make is whether to address these macroeconomic distortions in one go — via a shock treatment package of the kind that Argentines have come to know and fear — or more gradually. Both courses have their merits, and Mr Macri’s team of well-regarded economic advisers is reportedly divided on the issue.

Certainly, Argentina will need to have recourse to multilateral financial support at some point — including, presumably, the International Monetary Fund, even though the IMF is indelibly associated in Argentine minds with the country’s calamitous 2002 debt default and devaluation. So far, Mr Macri has said only that he would start to remove capital controls immediately after his inauguration on December 10.

Mr Macri also faces considerable political challenges. He lacks a majority in Congress, although this may not present an insurmountable barrier to the passage of legislation.

In the lower house, with 257 seats, his coalition has more than 90 deputies, and he may be able to count on the support of over 30 dissident Peronists to carry a majority. Mr Macri also lacks a majority in the Senate. But senators traditionally take their lead from Argentina’s powerful state governors who in turn negotiate directly with the president. So, on important issues, such as solving the holdouts issue, Mr Macri should be able to build the support he needs. He has form here, too. As mayor of Buenos Aires, Mr Macri managed to pass laws through the local legislature even though he also lacked a majority there.

Perhaps the biggest area where Mr Macri needs to effect change, though, is in Argentina’s investment climate. Financial investors have cheered Mr Macri’s rise and Argentine stocks and bonds have rallied on the prospect of change. But this rally has been a trader’s plaything. Mr Macri’s job is to convert Argentina into a destination for real money and foreign direct investment rather than a hedge fund speculation. For now, that is only a hope as it would mark a decisive change for a country that, during the past 100 years, is unique in having lost its former “rich nation status”.

But even in Argentina, as Ms Fernández remarked ruefully on her Twitter account last night, “nothing lasts forever.”

Fonte: FT

quinta-feira, 19 de novembro de 2015

Paris attacks must shake Europe’s complacency

There is an impulse in Europe’s political discourse, by no means the exclusive property of the left, that assumes nothing bad happens in the world without it being somehow the fault of the west in general and the US in particular. This is the mindset that casts Saddam Hussein as a victim, Hugo Chávez a hero and Russia’sVladimir Putin as a bulwark against Nato expansionism. The mass murder of Parisian concertgoers and Russian tourists may be crimes, but they are surely also the product of unprincipled great power intervention.

Listen to Jeremy Corbyn. The leader of Britain’s Labour party cannot censure the outrages of extremist jihadis without reference to the supposed crimes of the US: the siege of Falluja, say, or killing rather than arraigning Osama bin Laden. “We have created a situation where some of these forces have grown,” was Mr Corbyn’s reflection on the slaughter in Paris.

There is no shortage of criticisms to be made of the west — and they do not start or end with the invasion of Iraq. I find it shocking that Saudi Arabia is still treated as a staunch ally even as it exports the extreme version of Islam that informs the murderous credo of the jihadis. Then there is a welcome afforded Egypt’s president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi whose violent repression of the Muslim Brotherhood opens the door to Isis. With its oil and autocrats, the Middle East is a graveyard for anything pretending to be a principled foreign policy.

None of these hypocrisies can be held up in exculpation of the tyranny of the self-styled Islamic State. Those who think it better to explain than condemn forget that by far the greatest number of victims of Isis’ crimes are fellow Muslims in Iraq, Syria and, most recently, Beirut. Or that the caliphate replaces liberty with theocratic intolerance, subjugates women and murders homosexuals. The idea that the west should shoulder blame rests on a corrosive moral relativism blind to the essential evil of those who kill and maim. Indiscriminate murder is wicked. It demands unvarnished condemnation. Full stop.

You could ask whether anyone cares what Mr Corbyn thinks. The Labour leader’s formative memories are of the Vietnam war and the nasty campaigns waged by the CIA in central and Latin America during the 1970s. He has not stepped out of the time warp. He will never be prime minister. Even Fidel Castro thinks it is time to move on.

Yet Mr Corbyn’s response illuminates a broader strand of European thinking — a complacency that takes for granted the Enlightenment and has sapped the willingness to defend its essential underpinnings. Somehow it is easier to blame the west than to admit that there are those for whom freedom, tolerance and the rule of law are natural enemies.

We saw this when Mr Putin overturned the continent’s postwar security order by sending his army into Ukraine. The reaction of many on the right as well as the left was to mutter that the fault lay with Nato’s decision to welcome the new democracies of eastern and central Europe.

There are many more who have decided in the wake of Edward Snowden’s revelations that the principal threat to Europe’s freedoms comes from the electronic “snooping” of domestic intelligence services rather than from jihadis wielding Kalashnikovs and wearing suicide vests. Hopefully the balance will shift somewhat in the aftermath of the Paris attacks.

The original sin was the assumption that the end of the cold war did indeed mark the end of history. The complacency straddled the boundary of economics and politics. Liberal markets would create permanent prosperity, while political pluralism would become the default system of governance. The international order would be remade in the image of European multilateralism.

The first of the illusions was shattered by the financial crash of 2008, but governments and electorates have held on more tenaciously to the idea that democracy is the natural destination of politics. When things have gone wrong — the terrorist attacks of al-Qaeda and now Isis and Russia’s revanchism — the instinct has been to treat them as exceptions. The curtains, though, have now been torn open, not least by the influx of refugees fleeing violent chaos on Europe’s periphery.

What is required is a readiness to fight. This means a lot more than simply sending more warplanes to attack Isis in its strongholds, though the case for fiercer military action is a strong one. Fighting means recognising that the values that form our societies cannot be taken for granted; that the postmodern order imagined after 1989 is at very best some way off; and that even as they confront the enemies of freedom and tolerance European governments must address deprivation and marginalisation within their societies.

This in turn demands a willingness to admit there will be costs. But then anyone who has glanced at the history of the 20th century will know that today’s liberties came at a price. Nor should we imagine that governments will not have to make ugly compromises — not least in Syria — if some order is to be restored.

Above all, it is time for Europeans to celebrate what they have built and recognise it is under threat. The streets of Paris this week have seen a heartening resolve not to be cowed by the murderers. If Europe does not stand up for its values, who else will?

Philip Stephens

Fonte: FT

Assinar:

Comentários (Atom)