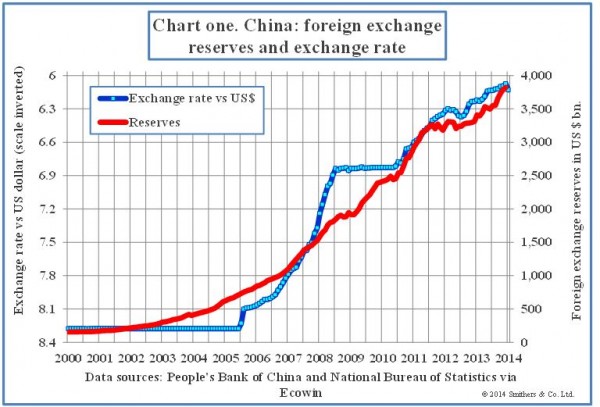

The Chinese government decided some years ago to keep its exchange rate undervalued by buying foreign currency and building up its foreign exchange reserves. The result has been dramatic. Reserves have risen by $3tn over the past seven years. This has occurred despite a strong rise in the exchange rate, as I show in chart one.

The rise in the reserves required China to buy dollars in exchange for domestic currency (renminbi) and, if no steps had been taken to “immunise” this, there would have been a dramatic rise in domestic liquidity with the probable result that inflation would have raced ahead. Immunisation can be achieved by funding a rise in exchange reserves through issuing long-term debt, but China’s bond market does not seem to have been sufficiently developed for this to have been done. Instead, the immunisation was achieved by requiring commercial banks to increase their deposits with the central bank.

This policy had its drawbacks. Lending to the central bank was less profitable than lending to commercial customers; as it reduced their profits, banks paid low interest rates on their deposits. This encouraged savers to put their money into an unregulated world of parallel financial institutions.

Having caused the rapid expansion of an unregulated parallel banking system, China now has to prevent it blowing up. This is likely to prove tricky as the rates of interest being paid seem way too high to be economic. As reported by the FT’sJames Kynge, the local view is that “you can get around 10 to 12 per cent by lending to a trust or around 20 per cent by putting it with an underground bank”.

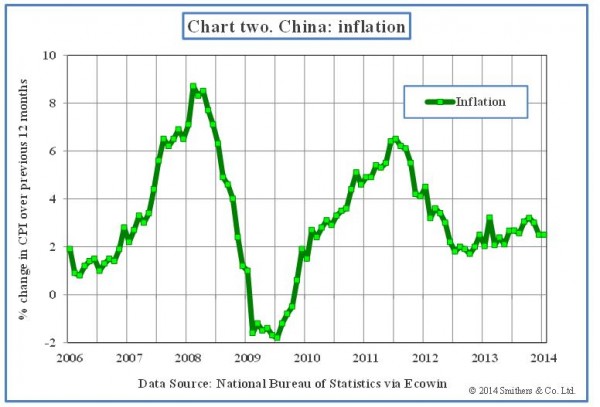

China grows more rapidly than the US and, according to an economic theory called the Balassa-Samuelson effect, it should therefore have a steadily rising real exchange rate and this, as chart one shows, it has had. The equilibrium real “risk-free” interest rate in China is thus lower than that in the US. As the US nominal rate is more or less zero, this can only be achieved if China has a more rapid rate of inflation than the US. At the moment prices are rising at about 2 per cent a year in China (chart two) which is almost exactly the same as in the US.

At the moment, as Mr Kynge quotes a shadow banker, “it is easy to borrow abroad at around 1 per cent annual interest … and bring it into the mainland”. Even with exchange controls, borrowing abroad can be achieved by over-invoicing exports. So foreign money comes in and either pushes up the exchange rate or the exchange reserves. If the former, it increases the profits on the carry trade; if the latter, it increases domestic liquidity and thwarts attempts by the People’s Bank of China to rein in excessive debt expansion.

The interest rates being paid in the parallel banking market are so far above the “risk-free” rate that they would seem to be very risky and should therefore result in lots of bankruptcies. If this happened, it would make the carry trade much less profitable, but might well set off a financial crisis.

Higher inflation in China would allow real interest rates to fall, and thus make the interest rates being paid in the parallel market less uncertain. This would be risky, as it is difficult to control a rise in inflation. However, I find it difficult to see what other solution is available.

In the past, as chart three shows, China appears to have used its exchange rate to dampen inflation. A lower and probably more volatile exchange rate would now seem to be sensible.

Andrew Smithers

Fonte: FT